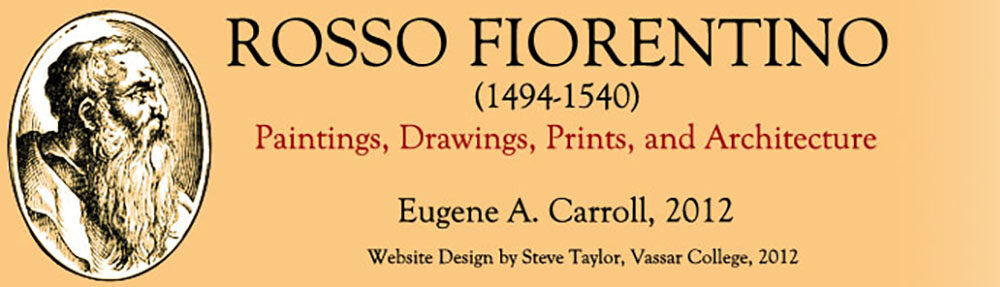

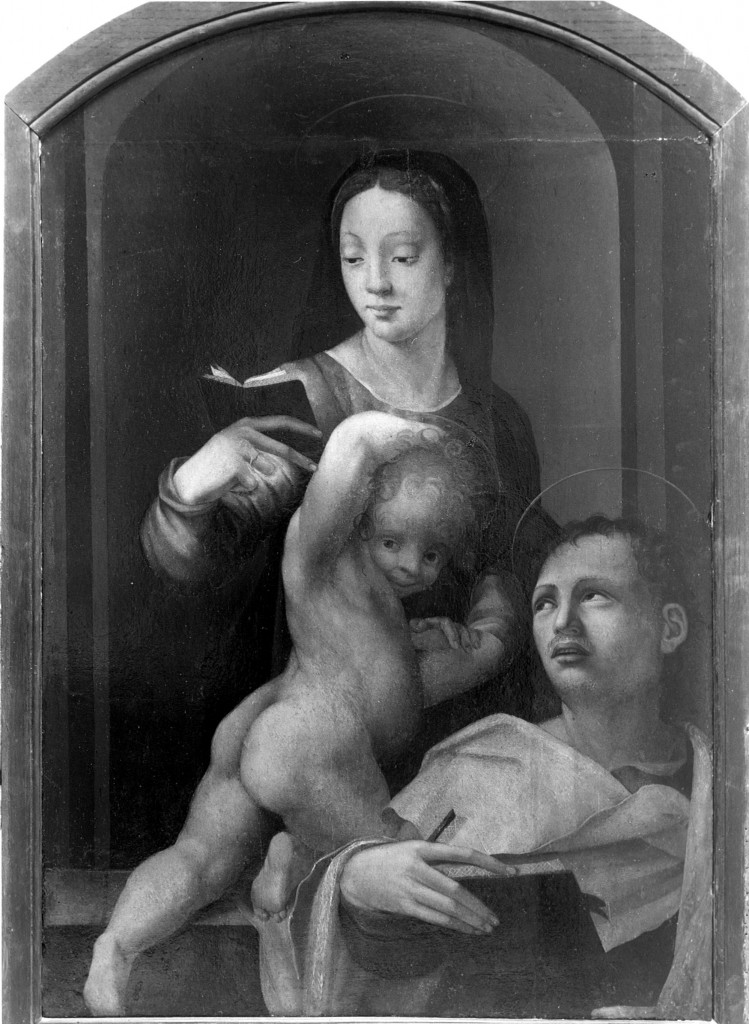

On 20 November 1513, when Rosso received the first payment for his Assumption of the Virgin (P.3; Fig.P.3a) at SS. Annunziata, Sarto’s Procession of the Magi (Fig.Sarto, Magi) and Franciabigio’s Marriage of the Virgin (Fig.Franciabigio, Marriage) were already completed, the latter two months earlier, the former two years before.1 Andrea had been working on his Birth of the Virgin (Fig.Sarto, Birth) probably only since September 1513,2 and outside, on the front of the loggia of the church, Pontormo was beginning to paint his Faith and Charity flanking the sculptured arms of Leo X.3 Rosso responded to the completed works by Sarto and Franciabigio, but the young artist did so only to a certain extent in sympathy with the stylistic terms established for this cycle of frescoes on the life of the Virgin by their two completed scenes. By comparison to these frescoes, the style of Rosso’s picture suggests that his ambitions were also to surpass their accomplishments, and to achieve, it might be supposed, a grander manner. For his Faith and Charity Pontormo seems to have entertained similar ambitions, and to have succeeded, somewhat to Andrea’s chagrin, when he saw, it appears from Vasari, Pontormo’s cartoons for this work.4

Rosso’s Assumption is on the south wall of the atrium immediately to the left of the main entrance from the loggia and diagonally across from the wall occupied by Andrea’s Procession of the Magi (Fig.Sarto, Magi), and the area in which he was painting his Birth of the Virgin. To the left of Rosso’s fresco was a blank space where a year later Pontormo would begin his Visitation;5 to the left of that area, on the adjacent east wall, was Franciabigio’s Marriage of the Virgin, probably already partly damaged by him because of his dissatisfaction with it.6 The area of Rosso’s fresco was, therefore, somewhat removed from the pictures that had already been completed in the eastern part of the atrium. It is quite possible that Rosso recognized the benefits of this somewhat isolated position, that it would be the last fresco of the cycle even after Pontormo had painted his.

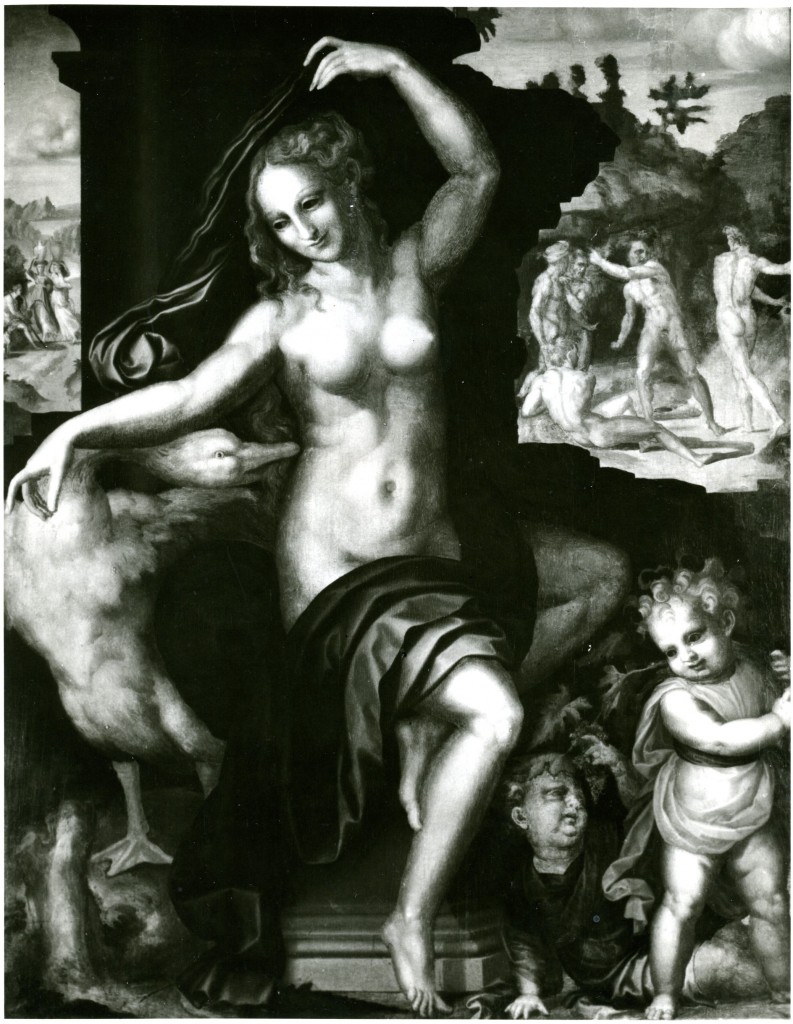

On the most fundamental level Rosso’s fresco differs from Sarto’s and Franciabigio’s in three significant ways. The point of view of the Assumption is lower and approximately at the level of the spectator’s eyes (Fig.P.3f); the lower half of the fresco is completely filled with figures so that there is no view into an extended space; and the figures are, in breadth and in height, larger, even, than the draped man in the very foreground of Sarto’s Procession of the Magi. In these respects no accommodation was made to what could have been recognized as basic similarities that would be shared to unify this cycle of frescoes. By ignoring these coordinating elements, Rosso was able to give to his scene an immediacy that is lacking in the other frescoes, including Andrea’s Birth of the Virgin. Not only do the size of Rosso’s figures and the absence of space affect the impression that the Assumption is up close to the viewer, but the low point of view also increases the illusion that the viewer is the spectator of an actual event. The small piece of drapery that falls over the raised lower edge of the fresco also heightens this illusion.7 Furthermore, standing close to the wall and looking almost straight up the viewer sees the Virgin and her ring of angels quite convincingly projected back—as an oval—into space with an expansive airiness and robust activity that contrasts dramatically with the dense grouping of the shuffling apostles below, all of whom stand forward of the Assumption itself. This illusion, which is bound to the position of the spectator and is less successful from a distance, suggests an interest in quattrocento art but without its general complementary regard for clear forms and spatial intervals. Although this illusionism could have been partly stimulated by the arrangement of the figures in Sarto’s Procession of the Magi, on which Rosso’s heavily draped figures certainly depend, the final effect of Rosso’s Assumption is not especially Sartesque. There is in its large forms, grave expressions, and compositional density a seriousness about Rosso’s work that distinguishes it from Sarto’s fresco of 1511. The procession of the magi’s retinue in Andrea’s painting could have been more formally arranged, but he preferred instead a colloquial randomness and a loose relationship of figures and space. Rosso’s picture is more formal, in spite of the restlessness of the apostles. This formality has been associated with Fra Bartolommeo’s, as in his Pitti Pala of 1512 (Fig.Pitti Pala). The figure of the Virgin has often been related to that of God the Father in the Frate’s and Albertinelli’s Last Judgement from S. Maria Nuova (Fig.Frate, Last Judgement). Still, there is a closeness of forms and a compositional compactness about Rosso’s fresco that is also not Bartolommeoesque. It is possible that Rosso has recalled here something of Masaccio’s realism, but not its geometry. Albertinelli, in his large Annunciation of 1510 (Fig.Albertinelli, Annunciation), had also looked back to the precedent of Masaccio, to his Trinity (Fig.Masaccio, Trinity) especially, and had seen in his art values still worthy of emulation. Albertinelli’s Annunciation, where again Masaccio’s example can be recognized,8 may, in its illusionism, its low point of view, and its ring of energetic angels above, also have had its effect on the conception of Rosso’s Assumption. The grouping of Rosso’s apostles suggests, even as disheveled, the arrangement of the apostles in Masaccio’s Tribute Money. Seen largely from the back walking into the picture, the apostle fourth from the left in Rosso’s Assumption recalls Masaccio’s tax collector in the center of his fresco. In addition, the individualized physiognomies of Rosso’s apostles suggest Masaccio’s. The generalized similarity of Sarto’s figures, and of Fra Bartolommeo’s, seems not to have been applicable to Rosso’s artistic intentions. He may, however, have appreciated Franciabigio’s more individual and dour faces in his Marriage of the Virgin of 1513.

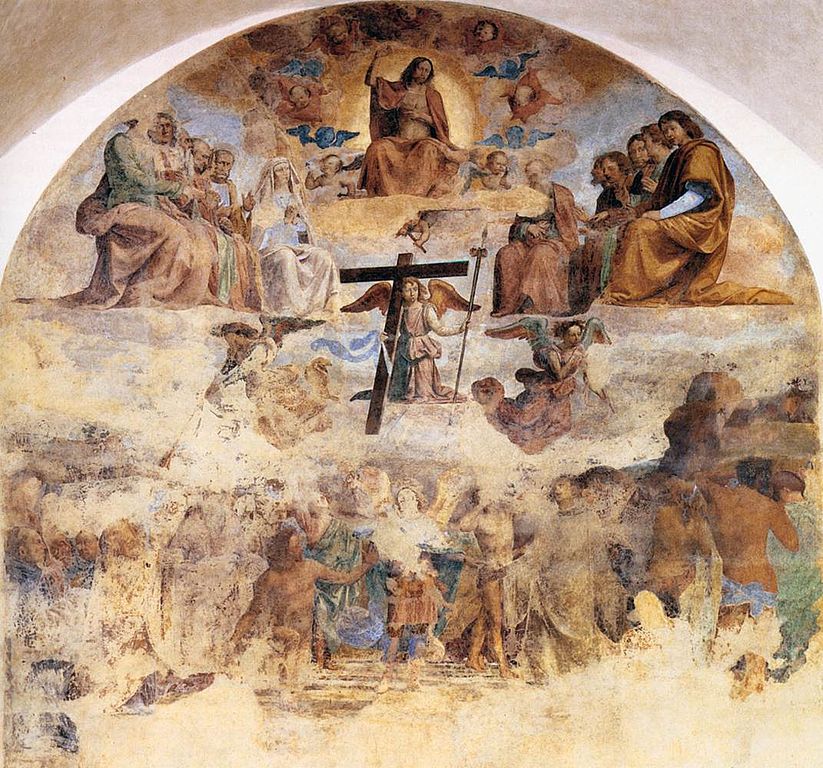

ROSSO AND DÜRER

Late in 1513 Rosso could have become interested in Dürer’s art. His prints were then available in Florence and just at that time one, his Birth of the Virgin woodcut (Fig.Dürer, Birth), had its effect, to a limited extent, on the conception of Sarto’s Birth of the Virgin. The very non-Italian absence of gestures and some of the postures, faces, and complex drapery of Rosso’s apostles suggest the study of Dürer’s Ascension (Fig.Dürer, Ascension) and Pentecost (Fig.Dürer, Pentecost) from the Small Passion of 1511, though the drapery is actually more an elaboration and enlargement of Sarto’s in his Procession of the Magi, which may also have been slightly influenced by Northern prints.9 But Rosso’s fresco suggests more of a response to Dürer’s images, not so much to particular stylistic details as to their grim seriousness and realism lacking grace. These qualities are, to some extent, shared with Masaccio’s severe style but not the latter’s clarity and good humor.

Compared to most contemporary art in Florence, Rosso’s fresco reflects a grandness of purpose that is comparable only to that of Fra Bartolommeo’s large altarpieces. Certainly these pictures must be recognized for their seriousness, and Rosso must have given his most concentrated attention to them. But they may have been too accomplished for Rosso, too developed to suggest further possibilities of expression. They may also have been too impersonal for Rosso, too remote from the actuality of experience. Here, Andrea’s art served Rosso’s inclinations better by suggesting to him something of the means to express the immediacy that we recognize before the Assumption. But Sarto’s Procession of the Magi appears, in spite of its richness of invention, to be filled with people who do not individually indicate much purpose. There is a casualness about them that, to Rosso, may have seemed too thoughtless. A similar kind of nonchalance appears even in Sarto’s stylistically more accomplished Birth of the Virgin. Rosso’s “opinione contraria” was not, it may be suggested, altogether irrational. The evidence of all his art shows that he had a more inquisitive mind than Sarto; he had also less strong conceptualizing powers than Fra Bartolommeo.

The Assumption of the Virgin is conceived first of all as an event that is experienced, witnessed, and attended by those within the picture without any regard for the spectator, who is not as informed as he might have been, from what Rosso presents about what is going on in the scene. No view is given of the sarcophagus, which is not always shown in pictures of this subject, nor any indication of the setting of this miracle, except that it is outside. None of the apostles turns towards us. The scene is dramatically and psychologically closed in upon itself. But its illusionistic devices, and the closeness of the figures to us, press upon us the event’s actuality in front of us and our existence before it. The meaning of the miracle is not taken for granted by the apostles; by some it seems uncertain, while others may simply not yet have seen it. The Virgin’s expression appears slightly anxious but also expectant; her gestures seem a little hesitant. Only the angels appear knowingly excited. The Assumption is not imagined by Rosso in terms of the flawless machinery of Fra Bartolommeo’s art, nor of the vibrant visual record of Sarto’s. The objective (and illusionistic) appearance of this Assumption reveals in its shuttling and quickly shifting relationships, of postures, glances and abundant draperies, an attitude that is more introspective, and even to a certain extent argumentative. The feelings of the apostles are not concordant and their postures and draperies are not harmoniously coordinated. The tonality of the picture is acidic, and if not unpleasant, somber in the effect of its grayish lavender, dark green, dark muted red, and ochre seen through a dusty chiaroscuro and accented by three large areas of light blue. Neither demonstrative nor expository—the hands of the apostles are almost all concealed thereby emphasizing by contrast the upraised arm of the Virgin—and yet large in its forms, the Assumption is both grand and private, the heir to the styles of Sarto and the Frate and yet very different in its personal use of them. Rosso’s fresco both enlarges upon the grand manner of their art and retreats from its public rhetoric; he has made specific what the Frate had generalized, and separately individual what Sarto had presented as collectively intimate. In the head of St. Jacob (James) at the far left the emotional effect is almost of madness, far beyond the fervor of St. John in the Tours picture but related to it. As St. Jacob may be the only apostle identifiable in the Assumption it is reasonable to assume that he can be associated with “maestro Giacopo frate de’ Servi” who persuaded Rosso to do the fresco. The head certainly suggests a portrait, as do the heads of the sixth and last two apostles on the right. The possible private meaning of the first figure and the unusual interpretation of the miracle of the Assumption bring to mind again the special characteristics of Fra Jacopo’s Madonna and Child with St. John the Evangelist. But the fresco does not show the earlier picture’s stylistic disparity. The Assumption, inarticulate as it may be in places—as, for example, in the incomprehensible structure of the Virgin’s raised arm and in the actual placement of the apostles in relation to each other and to the event that takes place above them—is stylistically consistent.

While Rosso’s “opinione contraria” towards the styles of other artists might, in the picture at Tours, be interpreted as containing a measure of incomprehension of them, this cannot be said to be evident in the Assumption. However, it must also be said, that incomprehension does not entirely explain the character of the earlier picture. For Rosso’s discontent must have originated in attitudes that were concerned with meaning as well as artistic ambition. Inchoate as any meaning had to be before it received pictorial definition, Rosso must have seen that the contemporary art in Florence did not meet the terms of his sense of some desired significance. Hence the juxtaposition of available styles in the Tours picture and the reshaping and personalizing of these styles into one of his own in the later Assumption. Though it is possible to say that no new historical style was created in this fresco, its particular style does seem a disruption of the order that is characteristic of the art of Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo.

Rosso, now turned twenty when the last recorded payment for the Assumption was made on 18 June 1514, was paid well for his fresco, and more than Franciabigio, at twenty-nine, was paid for his Marriage of the Virgin in 1513. Nevertheless, in June of 1515, exactly a year after the completion of the Assumption, Sarto was commissioned to replace it. Was it Andrea who was displeased with it and who would have given his opinion with some expectation of being heard at the Annunziata? Vasari says that Andrea was apparently jealous of the accomplishment of Pontormo’s Faith and Charity, the cartoons of which Sarto had seen in late 1513. After this Pontormo was no longer associated with Sarto’s shop. Pontormo’s frescoes themselves were finished at the same time as Rosso’s Assumption. Andrea may also have been jealous of Rosso’s accomplishment. There does seem to be some spite indicated by the fact that Sarto himself was going to replace Rosso’s fresco. But Sarto never actually returned to do any other frescoes in the atrium of the Annunziata. Pontormo was already being paid for his Visitation in December 1514. In September of 1515 Rosso was again at the Annunziata when he was paid for the execution of the arms of Leo X (L.9). Then on 18 April 1517, Rosso was commissioned another fresco in the atrium (see L.11), in the space “presso alla porta di Sancto Bastiano,” that is, most likely, in the only large area still available, to the left of Franciabigio’s Marriage of the Virgin. The guarantor of this new commission was again “maestro Jachomo di battista nostro priore.” Though the contract does not state what the subject of Rosso’s new fresco was to be, it could have been, as in an earlier commission of this space to Francesco Torni, “une visione della Natività di Nostra Donna con due Sibille et due Astrologii”—it does clearly state that “con questo patto che non si portando detto Rosso meglio che nel primo quadro da lui dipinto, egli non debba aver paghamento alchuno per detta dipintura….”10 That “primo quadro” must have been Rosso’s Assumption, but unfortunately it cannot be determined from this statement what was judged wrong with the first picture at this time. Probably not its execution as, so far as we can tell today, it has survived no less well than the other frescoes in the atrium. Possibly the size of the figures and low point of view of the fresco were thought inappropriate in relation to the compositions of the earlier frescoes. But these features had already been accepted by Pontormo for his adjacent Visitation. Perhaps the crowding and spacelessness of the Assumption were criticized along with the absence of certain traditional details such as the sarcophagus and a landscape. It is also possible that the uncertain emotional character of the scene and the unusual interpretation of its subject were not appreciated. Or does the implied criticism suggest instead Rosso’s uneasy personal relationship with Sarto and a history of it that may have gone back to when Rosso was first allowed to execute the Assumption at SS. Annunziata in the first place?

This first recorded censure of Rosso’s art was not to be the last, and in little more than a year came the refusal by a patron of another work, the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. The criticism of the Assumption was serious enough in 1514 and 1515 to warrant its replacement, but it was not strong enough that it could not eventually be excused and forgotten about, even if a reprimand still seemed called for in 1517. In 1550 Vasari praised the Assumption for the grace and foreshortening of the angels and for the postures of the figures and the beauty of some heads. The fresco would have surpassed all those in the atrium, according to Vasari’s judgement, but for two faults: the color, which did not have that “maturità di arte, con ch’egli poi crebbe co’l tempo,” and the overabundance of the drapery of the apostles. Rosso’s immaturity is noted here, and comparing the Assumption with his later works this might still be seen today. But now in retrospect the fresco appears not necessarily so much immature as intentionally different from the canonical contemporary works of Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo. Looking back from his own academically correct position in the 1540s, Vasari may also have recognized this but excused it, too, as caused by Rosso’s inexperience. He does not seem to have known that Sarto was commissioned to replace Rosso’s fresco.

The beauty of some of the apostles’ heads that Vasari commented upon cannot refer to any conventionalized scheme for them but rather to their quite extraordinary individuality. This is unlike Andrea’s kind of description where differences tend to be minimized, even in heads, like those in his Procession of the Magi, that are clearly portraits. The head of Rosso’s fifth apostle is almost entirely derived from Joseph’s in Franciabigio’s Marriage of the Virgin. Though no other head in the Assumption is so specifically like one of Franciabigio’s, it becomes apparent that Rosso’s attitude towards individualized heads is very much like Franciabigio’s. The heads by Rosso are larger, more boldly conceived, and are more forcefully portrait-like, but they share Franciabigio’s interest in the description of the different particulars of each physiognomy. In Franciabigio’s scene particular details more or less merely furnish the data of different appearances; in Rosso’s hands differences are emphasized and become the means of projecting very special kinds of character. However, insofar as Rosso’s youthful style approaches Franciabigio’s, it does so, probably, in regard to larger matters too. The lack of physical coordination of Rosso’s apostles and the absence of any fully understood contrapposto also recall Franciabigio’s figures in his Marriage of the Virgin. A closer equivalent to Rosso’s Assumption would be Franciabigio’s Last Supper of 1514 in the convent of S. Giovanni della Calza (Fig.Franciabigio, Supper).11 Rosso may not have known this fresco, which may well not have been executed until after his own mural was completed. But following from Sarto’s art and the Marriage of the Virgin of 1513 the style of Franciabigio’s Last Supper is much like that of Rosso’s Assumption. Where, however, Franciabigio achieves a kind of grand disorder that has a certain narrative effectiveness, Rosso has subtly shaped comparable irregularities so that within the broad and disciplined larger shapes of his composition—the rectangle of the apostles below and the foreshortened circle of the Virgin and the angels above—they articulate finer feelings, of glee, among the angels, and of transitory doubt, incomprehension and various states of awareness among the adults. For such a young artist the Assumption was a remarkable achievement and reflects a mind (and imagination) that was not simply contrary, or inadequate, as was Franciabigio’s occasionally, but which was intellectually questioning and artistically seeking for the forms that would hold the meaning he sought. In these respects Rosso’s attitudes were related more to those of Leonardo, Piero di Cosimo, and Michelangelo than they were to those of his most immediate predecessors, Andrea del Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo.

Vasari’s two criticisms of Rosso’s fresco, of its color, he wrote, would improve with the artist’s maturity; of its too abundant drapery of the apostles, he said nothing more. Neither criticism resulted in any remarks about the intent of anyone at the SS. Annunziata to have Sarto replace the Assumption. Nor did he mention that commission to Rosso in 1517 of another fresco of unknown subject in the atrium of SS. Annunziata that was never executed. For it Fra Jacopo was again the guarantor, as he had been three years earlier for Pontormo’s Visitation, the last scene painted in the atrium of the church.

As finely related by Costamagna in relation to Pontormo’s Visitation, the story that unfolds in these years is centered around the tastes of two clerics at the Annunziata: Fra Jacopo and Fra Mariano. Fra Jacopo, who in his wish to have the latest artistic inventions at the church, supported the young Rosso and Pontormo. Fra Mariano, who favored the slightly older and established Andrea del Sarto and Franciabigio, whom he chose to paint the Marriage of the Virgin. Difficulties also arose from the jealousy of Sarto over the extraordinary talent and achievement of Pontormo when he saw his cartoons of the figures of Faith and Charity to be frescoed on the façade of SS. Annunziata.12

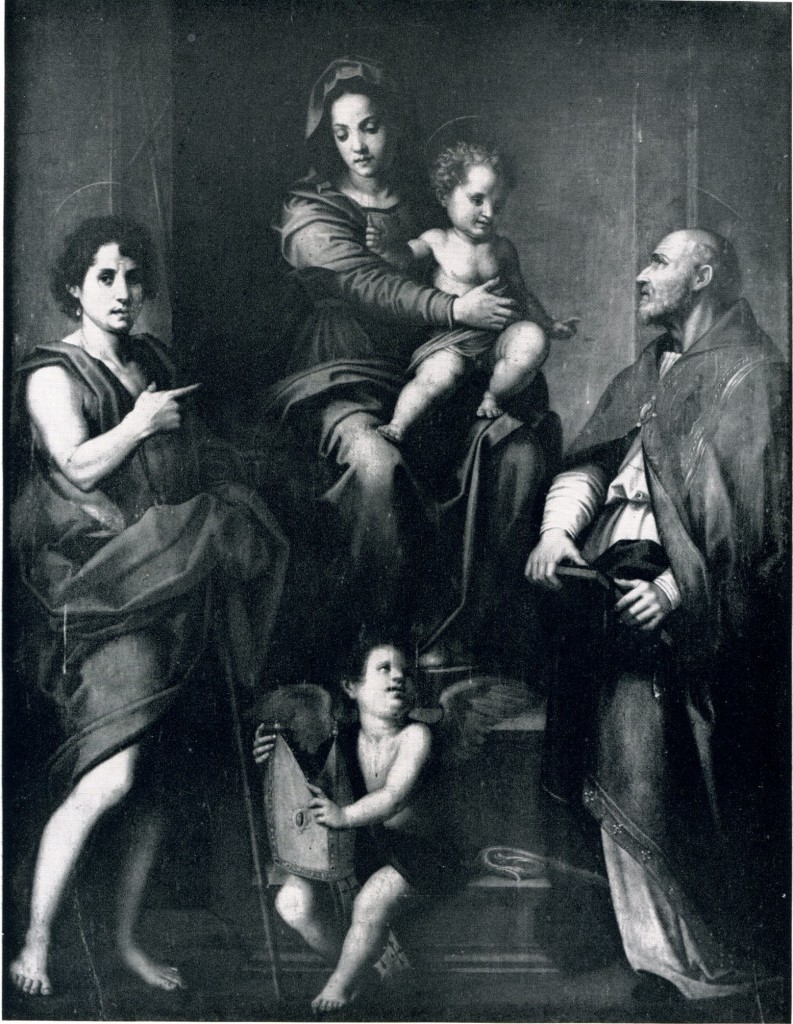

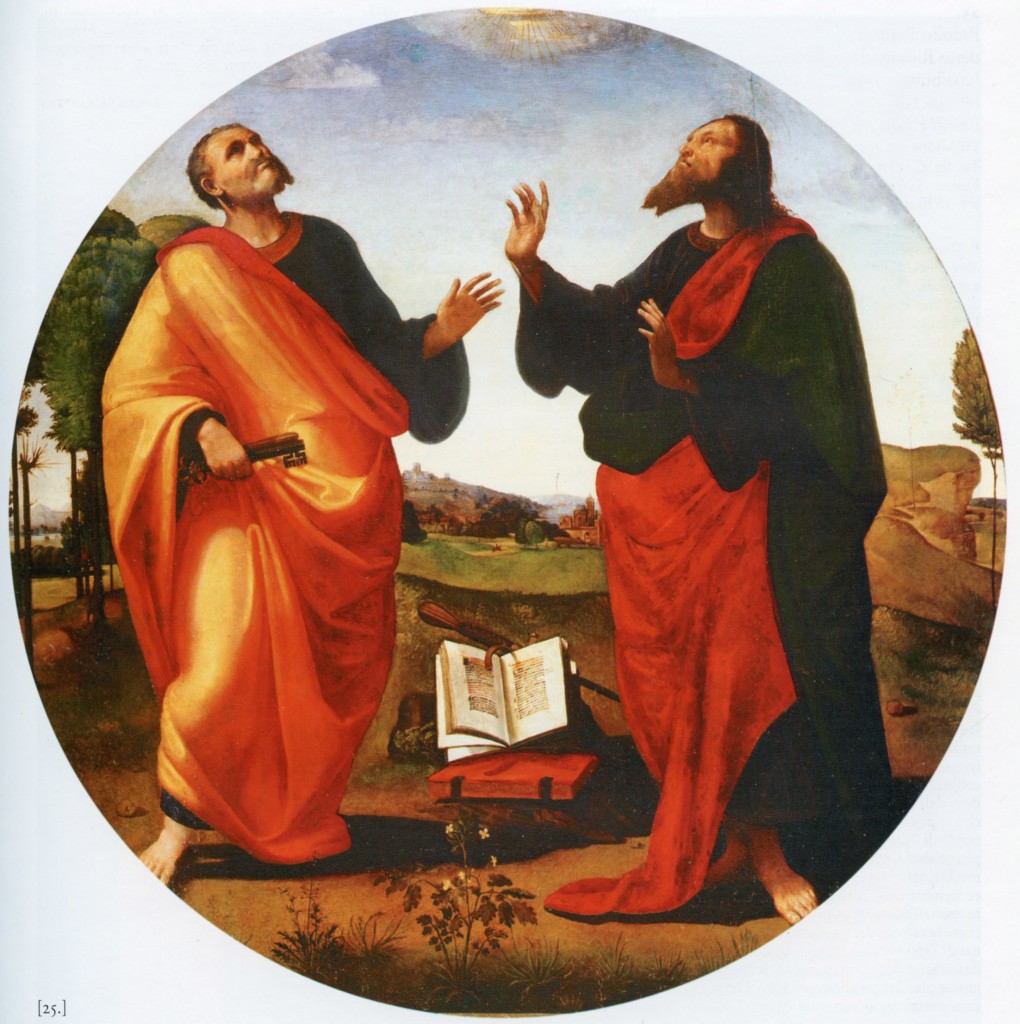

Unfortunate as these controversies were, they were ultimately resolved and forgotten by Sarto’s departure in May 1518 to spend a little over a year serving the king of France. In retrospect they may have been the consequence partly of the decision to have the frescoes of the Life of the Virgin on the east side of the atrium done by a variety of artists rather than one, as was the case with the five scenes of the life of Filippo Benizzi, all by the 24-year-old Andrea del Sarto in 1510, on the west side of the atrium. The distribution of these later scenes may have been to save money as the younger artists could be paid less. But it seems also to have been done in an attempt to get the most original works of art from the artists in competition with each other. Special concern with Rosso’s fresco by some of the friars may have come about because of the disappointment of the friars on the whole with Perugino’s Assumption of the Virgin of 1504–1506 (Fig.Perugino, Assumption) for the high altar of the Annunziata because, according to Vasari, it was tanto ordinario. The altarpiece was double-sided with the side facing the choir of the friars showing the Descent from the Cross that was left incomplete by Filippino Lippi upon his death in 1504 and finished by Perugino (Fig.Lippi-Perugino). The Assumption facing the body of the church was wholly by Perugino. So disappointing was the latter that the friars decided to turn the altarpiece around to have the Descent from the Cross face the body of the church. Eventually the entire altarpiece was removed to make room for the tabernacle of the Blessed Sacrament.

The subject of the Assumption of the Virgin was especially venerated by the Servite order because it was founded in 1233 on the feast of the Assumption when seven patrician Florentine men had a vision of the Virgin who told them to give up the world and devote themselves to eternal things and to serve her. Hence the Servite Friars’ choice of her Assumption for the high altar of their mother church and as the last scene of the sequence of scenes of the Virgin’s life in the atrium of the Annunziata. (They could have chosen the death or dormition of the Virgin.)

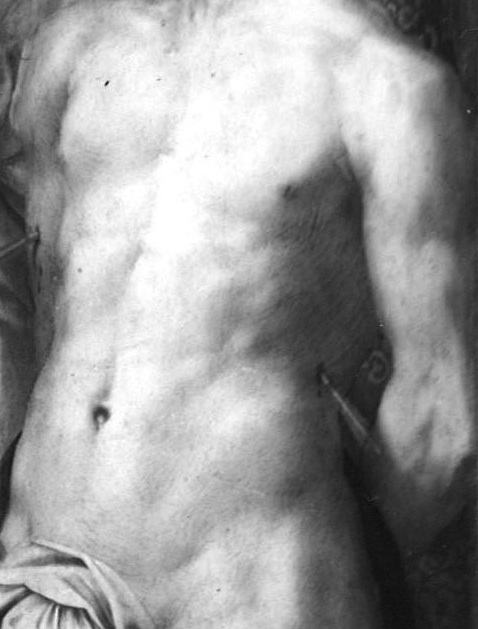

Perugino’s Assumption of the Virgin shows St. Thomas standing isolated from the other apostles in the center of the scene and in front of an empty and barely visible sarcophagus. From his shoulders hangs across his chest the string-like girdle of the Virgin, which she dropped to the doubting Thomas to prove the truth of her Assumption. This episode is not always shown in scenes of the Assumption, but its inclusion helped confirm the miracle of the ascent of the Virgin’s corporeal body to join her soul in heaven. At the Annunziata the depiction of this detail helps also to verify the appearance of the Virgin on the festival of her Assumption to the seven men who founded by her charge the mendicant order of the servants of Mary.

The other eleven apostles are arranged at either side of St. Thomas, most but not all looking up and five with simple gestures of reverence and surprise held close to their bodies. Two are old, bald or balding, and with long beards, one younger and bearded, and the others young. At the far right stands fully visible a young apostle looking up who is not gesturing but holds close to his body a large book in his left hand. He would be St. John the Evangelist in whose Revelations, Book XII, 1–5, appears the only biblical passage that has been interpreted as referring to the Assumption of the Virgin. This passage describes one of John’s visions: “And there appeared a great wonder in heaven, a woman… being with child… And brought forth a man child who was to rule all the nations…” For all their stylistic differences, Perugino’s scene is, in the program of its story, identical to Rosso’s Assumption of the Virgin, but for the absence of an empty sarcophagus behind St. Thomas. This is a detail, however, that is not always shown and does not appear in Perugino’s Corciano Assumption of 1513 (Fig.Perugino, Corciano) that is modeled upon the altarpiece made for the high altar of SS. Annunziata.

Hartt seems to be the first art historian to identify the violet band of drapery strung around the body of the lowest angel with a swag of it floating down above the opening between the heads of the central apostle and the one to his right, both looking up, as the Virgin’s girdle, looking like a sash rather than a string as in Perugino’s picture.13 St. Thomas would be the central apostle wearing a great green mantle and seen from the back. The tail end of his abundant drapery falls over the lower painted frame of the fresco, becoming a motif that leads the spectator’s glance from beneath the bottom of the fresco up into the scene and to the upward turned head of Thomas (Fig.P.3f). His seemingly small foreshortened head is placed slightly lower than the heads to the left and right. It is just possible that the green of his garment is related to its function as the symbol of Hope.14

Three of Rosso’s apostles hold books but two, held by the fourth and ninth apostles, are barely visible by how little is seen of them and by their dark color. However, the second apostle holds a large white book that is wholly visible. He stands next to the first apostle, the only one that bears emblems and other details that identify him as St. Jacob and as a pilgrim to the church and shrine of Santiago de Compostella. On his pilgrim’s hat, which all but hides his halo, he wears a scallop shell, the symbol of pilgrims to the shrine of St. James (Jacob), and a second badge that has yet to be identified. This badge seems also to appear on the cover of the book held by the fourth apostle. St. James holds a pilgrim’s staff. That he should be identified with Fra’ Jacopo, who was instrumental in getting the nineteen-year-old Rosso the commission of the fresco, appears obvious. St. James was thought to be the author of the Protoevangelium of St. Thomas that tells the story of the early life of Mary, which, though not narrating the Assumption, would most likely have been a text revered by the Servites. The identity of the second apostle is not so obvious, but the prominence given to him by his very large white book may well indicate the author of Revelations with its vision associated with the Assumption, St. John the Evangelist. It is he who appears in Rosso’s early painting for Fra’ Jacopo for reasons that could not be understood but that may well be related to why he is also given special recognition next to St. Jacob in Rosso’s Assumption, that is a special reverence by Fra’ Jacopo for St. Jacob (James), his namesake. It is likely, too, that it was the friar’s knowledge of theology that made Rosso aware of another story of St. Thomas who was not at the Assumption but appeared later, asking to have her tomb opened to prove her ascent. It was then that the Virgin, feeling pity for the troubled apostle, dropped down her girdle to him.

MADONNA AND CHILD WITH SAINT JOHN THE EVANGELIST

Costamagna writes of Rosso’s Assumption of the Virgin: “L’oeuvre, visionnaire, ne fut comprise de ses contemporains…”, an aperçu that may connect the fresco to St. John’s vision without illustrating any obvious references to it. Rosso’s earlier picture for Fra’ Jacopo, even in its Tours copy (Fig.P.2Aa), may intend, as commented earlier, a similar experience beyond the ordinary.

Knowing that the fresco was disliked by some at the church requires that we attempt to explain why this was so. But this need not determine our assessment of the fresco. Five decades later Vasari wrote that there was too much drapery and that the coloring of the picture was immature in comparison to the “skill that he acquired with time.” This could not have been known to the friars at the time. Still, Vasari praised the ring of angels, and found the poses and heads of some of the apostles “more than beautiful.” Today the fresco looks imposing for the grandness of its conception and the sense of dense and varied thoughtfulness of the apostles and of the Virgin herself, all unified by the chiaroscuro of its masses and the lavender atmosphere surrounding the Virgin in which the angels romp below the luminous upper region into which the humble Virgin is being transported. Rosso’s success with chiaroscuro and atmosphere in fresco is a remarkable feat. Dispensing with a tomb and with any joyous gesticulation for the apostles leaves the Virgin alone to extend her arms in response to what is happening to her. Even Thomas does not reach up to receive the Virgin’s gift. More than any other artist, but without quotations from him, Rosso’s painting recalls Leonardo in the diversity of the reactions of the apostles and in the tight rectangular grouping of them as the foundation above which the circle of the Assumption arises.

The last payment for the fresco was made in June of 1514. In December Pontormo was first paid for his Visitation next to Rosso’s fresco. By the time Pontormo began to execute his fresco he could have seen how Rosso had dealt with chiaroscuro and atmosphere. His fresco may reflect his study of Rosso’s in these respects, although he had handled the fresco technique already well in the large but shallow San Ruffillo Madonna (Fig.Pontormo, San Ruffillo) without the depth and atmosphere of his Annunziata fresco. Rosso, too, had earlier done his lost fresco of the Dead Christ in the tabernacle at Marignolle when he was nineteen. It was not a technique he liked, as Vasari commented. In this respect he was also like Leonardo.

After the Assumption of 1513–1514 there survives no major painting by Rosso from before 1518, the date of the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. As mentioned earlier, on 20 September 1515, Rosso was paid for executing at SS. Annunziata, a coat-of-arms of Leo X “con due fanciulli,” a lost work that was painted over the entrance to the Chiostro de’Morti (L.9) and, therefore, may have been designed to relate to the arms, also destroyed, of Cardinal Pucci “con due figure” of 1513 (L.8) on the other side of the long façade of the Servite church.

The same year, for the entrance of Leo X into Florence on Friday, 30 November on his way to meet Francis I in Bologna, Rosso designed a triumphal arch that was built at the Canto de’ Bischeri, where the Via dell’Oriuolo and the Via del Proconsolo meet at right angles as they enter the Piazza del Duomo near the east and south apses of the church (L.12). It was one of seven triumphal arches designed by various artists erected for this occasion, each devoted to one of the cardinal and theological Virtues, as attributes of Leo, with an eighth arch showing them all together as the summation of his virtues. Vasari says only that Rosso’s was “un arco bellissimo … con molto bello ordine e varietà di figure.” It is more fully known from several contemporary descriptions, by Gualtieri Panciatichi, by Luca Landucci, by Giovanni Cambi, and by Guglielmo de’ Nobili. The structure, dedicated to “green” Hope, as noted by de’ Nobili, was square and as tall as the houses around it, with its huge crossed arches aligned with the two streets that entered the Piazza del Duomo at the Canto de’ Bischeri. It was probably big enough to allow the procession to pass through it, coming from the Via Proconsolo and turning, within the structure, in the direction of the cathedral. Painted in imitation of porphyry, it was articulated with a large number of Doric pilasters that supported a cornice and, on one side at least, facing the Via Proconsolo most likely, a pediment with a gold plaque inscribed: SPES EIVS IN DOMINO. L.X.P.M. (His Hope in God).15 Above one of the large piers, perhaps in the attic of the arch, on the Via Proconsolo side probably, was a painted scene, imitating an antique relief it would seem, showing Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the Fiery Furnace, and, across from it, another painted relief of Moses and Aaron Turning the Waters of the Nile into Blood. On the pier at the left, between pilasters, was probably a feigned sculptural group of Elisha Curing Naaman’s Leprosy, and, on the right pier, Jacob and the Angel. Probably on the west side of the arch was a feigned relief showing Noah Inside the Ark Awaiting the Return of the Dove, which could have been seen looking back as the procession passed through the arch. On top of the arch was a sculptural group, in stucco or plaster and cloth, of the Sacrifice of Isaac.

The program of the figure groups and the scenes on the arch, related to the theme of Hope designated for the entire structure, would have been devised by those who programmed the entire entry, perhaps Jacopo Nardi and Marcello Virgilio Adriani, under the direction of Alfonsina Orsini, the widow of Piero de’ Medici and mother of Lorenzo, the recently appointed Captain of the Florentine Republic, and Giuliano Tornabuoni, the Protonotary Apostolic. Drawings for the triumphal arches and other decorations were already made by 3 November; so, too, must the program have been devised by then.16 The Old Testament subjects that are known to have elaborated the theme of Hope assigned to the arch for which Rosso was responsible may have been its complete figured decoration; the sides not facing the procession need not have been elaborately decorated. All but two subjects were, it can be supposed, used on the façade that faced the Via Proconsolo, and the group on the top of the arch probably also faced the same way. Most appropriately the scene of Noah waiting for the return of the dove would have appeared where the Pope and his cortege would see it looking back upon the arch as they emerged from it on the way to the cathedral. No evidence has been found that shows the appearance of these groups and scenes. The general antique style of the entry prescribed the general aspect of Rosso’s arch and it is probable that the size, plan, and order of his arch were determined for him in accord with a diversity wanted among the eight triumphal arches. The porphyry color could also have been assigned but its use with gilt garlands of pomegranates and pine cones suggests a personal artistic decision. Its many pilasters were mentioned by Landucci who thought this arch was the richest of the triumphal arches of the entry, and Panciatichi thought that Vitruvius would have awarded the prize to Rosso’s arch before all the others. It was Rosso’s first work of architecture and while not permanent it was so successful to be praised as the finest of the arches that day by at least one knowledgeable spectator. It can be noted that Rosso, along with other artists, may have walked in the procession honoring Leo X to be honored themselves for their artistic achievements in this grand triumphal entry and to the glory of the city of their origin and of the Florentine pope.17

For the return of Leo X from Bologna on 22 December 1515, a more modest series of decorations was created. At the Porta San Gallo (Fig.Porta San Gallo) a triumphal arch was erected similar to the first arch that greeted the pontiff when he entered the city the previous month. Rosso was paid for the decoration of the custom officer’s station (gabellino) before the arch and of the area between the Porta San Gallo and the forward gate (antiporta). What ornamento Rosso created is not known (L.13), but it may not have been only ornamental decoration. One recollection reports that the paintings of this decoration at the Porta San Gallo were done on canvas and were of scenes from the Old Testament and perhaps antiquity on the theme of Peace to match the dedication of the triumphal arch. It is still to be discovered what surfaces existed in the area between the Porta San Gallo and the antiporta to which Rosso’s paintings on canvas would have been attached.

ANGEL PLAYNG A LUTE

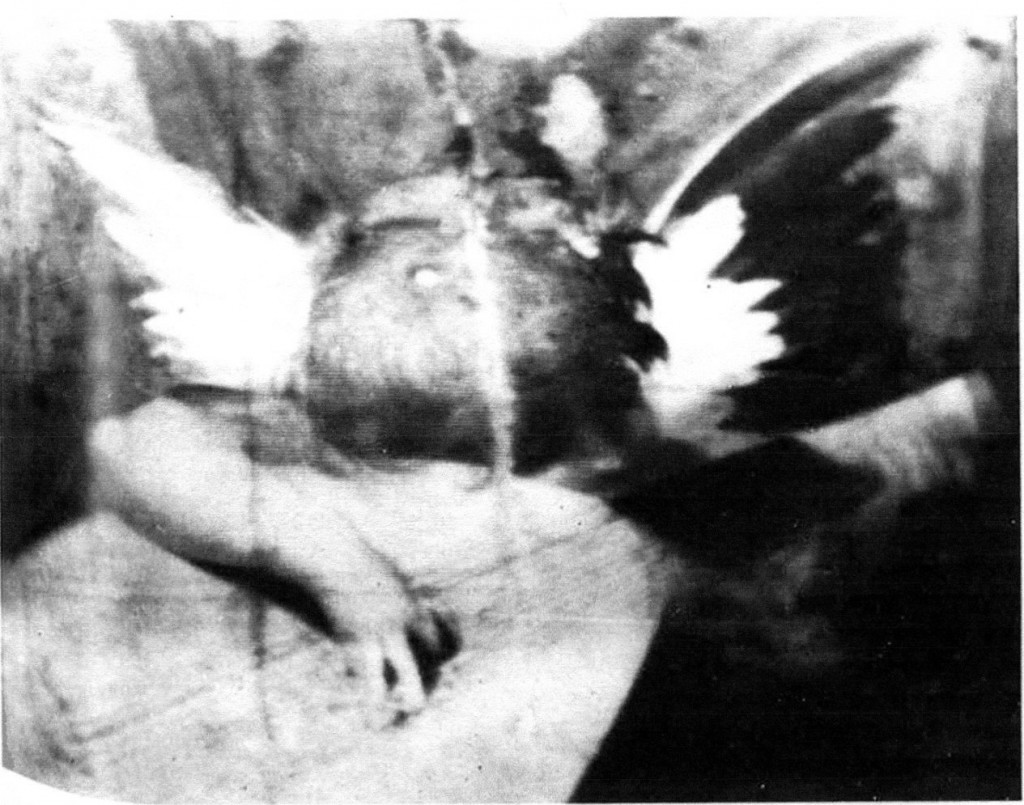

Rosso’s small Angel Playing a Lute in the Uffizi (Fig.P.4a) may have been done in 1514 or 1515 soon after the Assumption of the Virgin whose angels it resembles. Like that fresco the small panel carries with it a complex critical history. From around 1600 the small painting would have been liked for its charm and for the intimate appreciation it offers of Rosso’s winged child intensely concentrating upon the playing of his lute, an instrument almost too large for him to handle. It was not until 1965 that it began to be largely recognized that it is not the work that Rosso conceived. For such a small independent work of art of this subject in early sixteenth century Italy seems as unlikely as it is unprecedented. Only the two angels from the bottom of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna cropped from the altarpiece and first made popular in the twentieth century is an image of similar charm and concentration.

The greenish and gray tonality of the small panel also suggests the color and shading of the Rosso’s fresco while the red-orange of the inner parts of the wings recalls the color of the drapery in the lower right corner of the copy of Rosso’s early lost painting at Tours (assuming that the color of the lost original is preserved here).

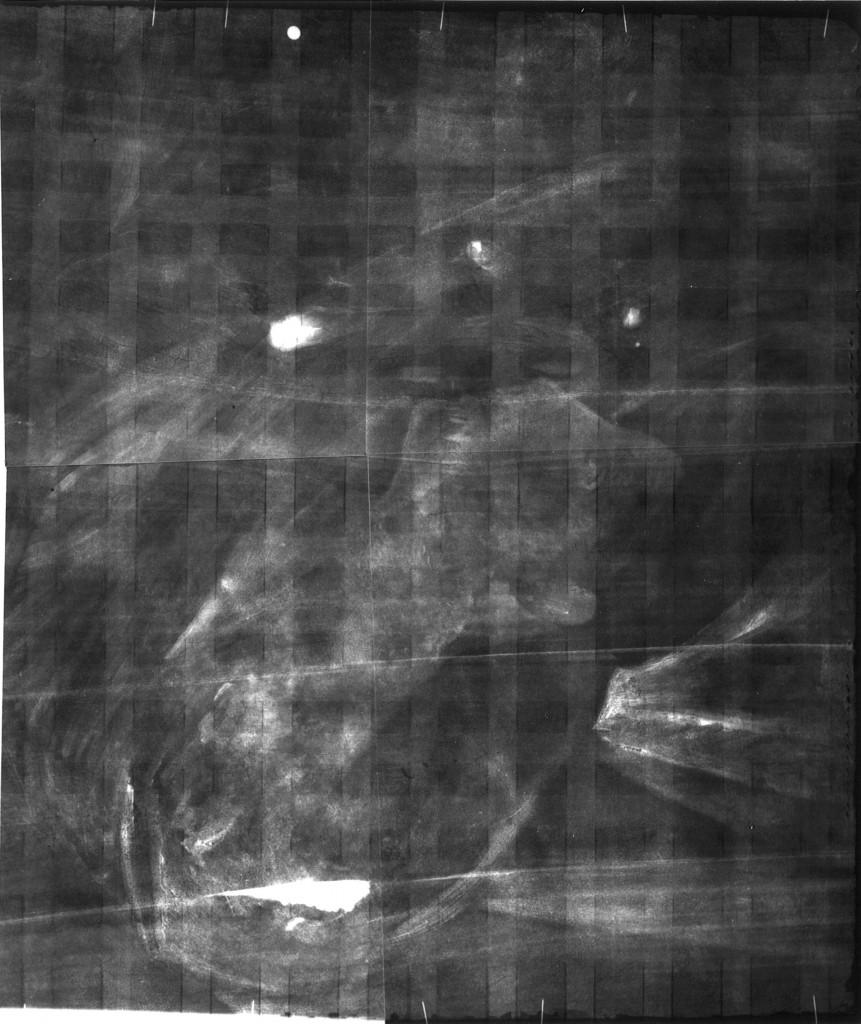

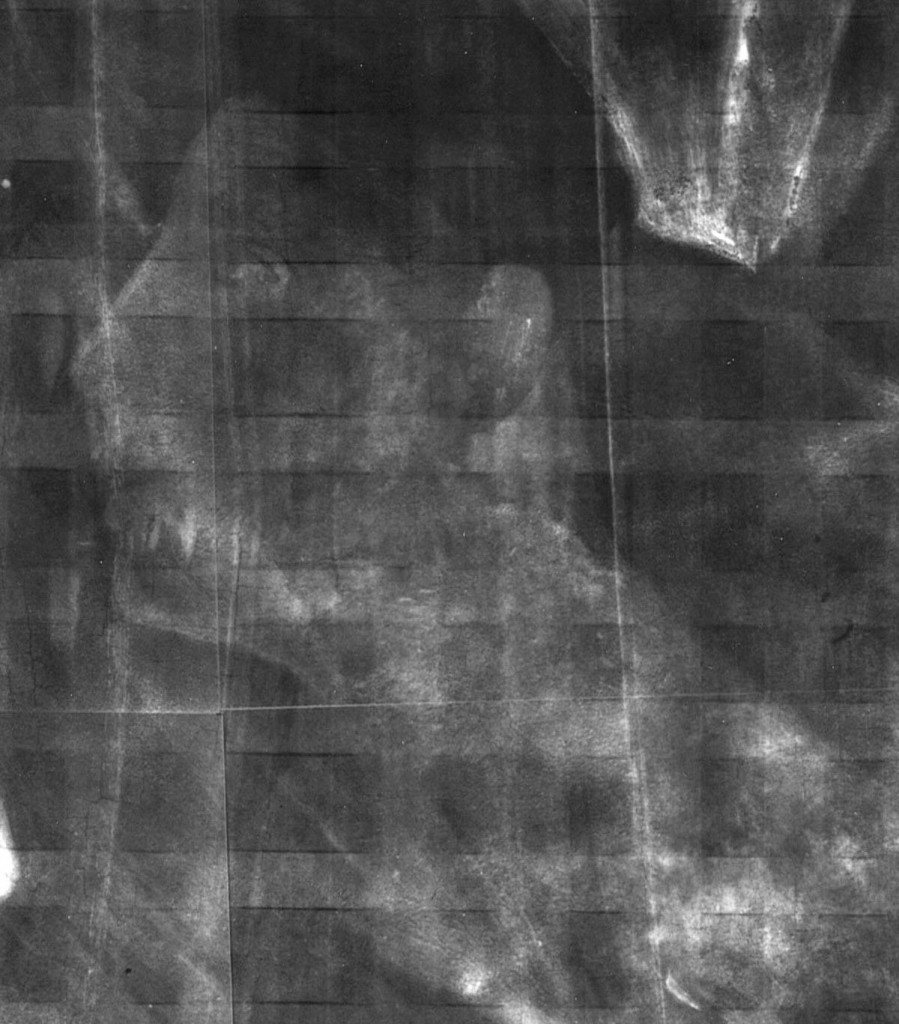

A reflectograph of the Angel Playing a Lute made for and published by Antonio Natali in 1985 (Fig.Reflectograph85) shows that the small panel is a fragment of an altarpiece that had a male saint with a staff at the left of the angel and St. Catherine of Alexandria with her wheel a the right, of which, however, only the staff and the wheel are found under the repainted background of the Uffizi painting. These details are just enough to suggest the one female saint whose martyrdom was to happen with a wheel of sharp blades and a male who generally carried a staff, among whom are the pilgrims St. Roch and St. Jacob (St. James), although St. Onofrius was suggested by Natali because of his appearance with a staff at about the same angle in Sarto’s Sarzana Altarpiece (Fig.Sarto,Sarzana) with St. Catherine and her wheel across from him. But St. Jacob carrying a staff at a similar diagonal appears with the youing and beautiful St. Catherine kneeling near a fragment of her wheel in Ridolfo Ghirlandaio’s Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria of 1507–1508. Higher in the altarpiece would have appeared the Madonna and Child raised upon a pedestal with steps before it, as in Fra Bartolommeo’s altarpiece of 1509 in the Cathedral at Lucca (Fig.Frate,Lucca) and in his Pitti Pala of 1512 (Fig.Frate,Pitti), or as in Rosso’s own S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece of 1518 (Fig.P.5a).

The original altarpiece could have been cut up by Rosso around 1520 when he did his Portrait of a Young Man in Washington (Fig.P.8a), painted over part of the image of a young and beautiful woman with her head in profile to the left (Fig.P.8d; Fig.P.8e). Compared to the few early heads in profile by Rosso the head under the portrait can be recognized as his and related to the Angel Playing a Lute and to the details that lie under the repainted background. The profile head could be the remainder of the figure of St. Catherine of Alexandria facing the Virgin and Child, possibly in a Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria painted by several artists in Florence in the first two decades of the sixteenth century. In these same years she also appears simply standing with with other saints as in Granacci’s Madonna in Glory with Four Saints of around 1512–14 (Fig.Granacci,Glory) and in pictures of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.18 But the Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria seems to have had special favor in the early Cinquecento with older women seeking husbands and in honor of women of various ages who had not yet married and became devoted to St. Catherine of Alexandria who had refused to marry the Roman Emperor Maxentius (and paid for it with her head).

Rosso’s full name and the date 1521, discovered on a second and finer reflectograph made in 1996 and also published by Natali (Fig.Reflectograph96), could have been added to the panel by Rosso, assuming that these inscriptions are authentic, late in his stay in Piombino where he has taken the small untrimmed fragment that he cherished in his luggage. Falciani wondered how such finely painted inscriptions by Rosso could have survived in the severely damaged and repainted section of this small picture. Perhaps the name and date were added by the restorer who straightened the edges of the fragment and reinvented it as an independent small picture, possibly intending it for the plan of a hanging, around 1600, of the pictures in the Tribuna of the Uffizi.

Records of this lost altarpiece have never been found. But from the width of the two parts that were cut from it, in Florence and in Washington, it must have been at least as large as the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece (172 x 141). How finished it was is not clear, but evidence of flesh tones indicates that the head was not simply a sketch on the panel but had been worked up to some extent. Like the altarpiece of 1518 the lost work is likely to have had at least four saints and maybe six instead of just the two indicated by the details in the reflexographs, as Ridolfo Ghirlandaio managed to accommodate in his Mystic Marriage to St. Catherine of Alexandria in the Instituto delle Quiete outside Florence (Fig.Ridolfo,Marriage).

It may be meaningful that Vasari, who in general is very accurate in the order of presentation of Rosso’s Florentine works as compared to the documentary evidence, seriously misplaced only the altarpiece of 1518, situating it immediately after the Assumption of the Virgin of 1513–1514. There may have been some confusion here between the facts of an earlier commission and that of the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece. The earlier altarpiece would have been begun and then, perhaps still unfinished, abandoned. After a piece of the panel had been cut out for the making of the Portrait in Washington, the Angel Playing a Lute was fashioned from a nearby section of the original altarpiece. The destruction of this altarpiece may indicate still another instance of displeasure with Rosso’s art, though it is not possible to see in this small painting what the nature of the dissatisfaction could have been. If the saint with a staff was St. Jacob, the altarpiece may have been commissioned by Fra’ Jacopo for SS. Annunziata and then put aside at the time of the disagreement over the success of Rosso’s Assumption and Sarto was chosen to replace it. Another connection may lie with suit made against Rosso by Jacopo di Leonardo da Colle probably initially before 18 December 1517, for the debt of eighty-six lire piccoli in the court “nell’arte et università deli Spetiali della città di Firenze” and then, when not successful there, to the higher Tribunale di Mercanzia (see DOCS. 3–6 and L.11). As the first court, related to the guild in which artists matriculated but also dealt with pharmaceutical matters (speziali) that included the purchase of pigments, and the second with mercantile transactions, it may be that Rosso left the altarpiece unfinished because he ran out of the funds to buy the supplies to paint it. Perhaps the altarpiece was not commissioned but was started by Rosso to prove his talent and training after the controversy over his fresco and then abandoned when he had convinced the spedalingo at the hospital of S. Maria Nuova to commission an altarpiece from him of about the same size on 30 January 1518.

The apparent self-contained image of the musical angel has not unjustly suggested to many observers before the reflectographs were made that the picture is complete as we now have it. But considering how it was re-conceived as an independent picture and repainted in places to achieve this end, it can, and surely must, also be studied for what it represents of the altarpiece of which it had been a part. In Fra Bartolommeo’s altarpiece of 1509, the single angel playing a lute (Fig.Frate,Lucca,Angel) has an open pose and his head is turned slightly up and to the side directing his attention outward. The same is true of the putto in Sarto’s Madonna of S. Ambrogio of around 1515 (Fig.Sarto, Ambrogio).19 But this is not the way in which the two little angels beneath the Virgin are depicted in Rosso’s altarpiece of 1518. Huddled together they are looking down at the book they hold between them, the one in profile at the right explaining to his companion the meaning of the text that has their attention and that may be implied as related to the subject of the disputation above between John the Baptist and Jerome. Rosso’s single angel is also shown intently concentrating on what he is doing so that his separation from the altarpiece to which he once belonged is hardly noticeable.

Rosso’s putto is characterized as a child who is intensely interested in what it is doing. He is neither simply one of the Frate’s precocious children nor Andrea’s inexpressive pudgy infant holding St. Ambrose’s large miter, although Rosso’s angel does share certain traits with them. Rosso’s figure holds a lute far too large for a child, as St. Ambrose’s hat in Andrea’s picture should be too large for its little angel to manage although he carefully grasps it as he looks up at the standing saint. But unlike the much smaller lutes that are held by Fra Bartolommeo’s angels in the Lucca altarpiece and the Pitti Pala, Rosso’s huge lute is held close by the angel whose cheek is pressed against the edge of the instrument that completely hides his body. Holding it up against his cheek and hidden ear, he reaches over it to pluck its strings with his right hand over the decoratively carved circular grill of the soundboard. The other, foreshortened arm comes from behind to support the instrument’s long neck from below. The putto looks at his fingering and listens to the sound he makes through the hidden belly of the lute. The kind and degree of intimacy suggested here might bring to mind the children that appear in fifteenth-century paintings and sculpture. However, although Rosso’s angel appears deeply pleased, he is not playful, nor does he seem to be entertaining us. Instead we look upon a very private moment of self-absorbed fulfillment and satisfaction. The concentrated joy of the child finds its pictorial equivalents in the intertwined loops of his hair, in the intensely arched wings that spring to either side, and in the dark shadows of the eyes. It is, furthermore, indicated by the beautiful spatial counterpoint of the arms seen in relation to the muted geometry of the lute, by the bright and deep colors of the picture and by the strong raking light that models the forms and rhythmically punctuates the design of the picture at the same time that it implies the fleeting moment of the putto’s activity. Even in such a small painting, and a fragment at that, Rosso’s intentions are revealed, as they are by his large Assumption of the Virgin, to be of a personal and introspective kind. By the slightest shifts of relationships and of emphasis, the formal, decorous putti of Fra Bartolommeo and Andrea’s gross and unruly children have become, in Rosso’s painting, a creature with a special poignant charm.

From what can be seen of the clear profile and of the expression of the open mouth of St. Catherine of Alexandria in the x-radiograph of the National Gallery portrait suggests the comparable charm of a beautiful young woman. Perhaps that head had also something of the crisp linearity and precise form of the hair and face of the musical angel, characteristics that may have been found throughout the lost altarpiece together with the introspection just suggested.

What cannot be concluded with certainty is that the picture was judged unsatisfactory and thus belongs with the history of disappointment that includes the early Assumption and the later altarpiece commissioned by the spedalingo of the hospital at S. Maria Nuova. If, however, the altarpiece was made to prove that he would do better than expected, recalling the wording of the contract for the second fresco that Rosso was to paint in the atrium of SS. Annunziata, then perhaps it was left unfinished where it proved that point. This could be a factor in how it came about that that spedalingo commissioned Rosso to paint the altarpiece. Another possibility, not necessarily related to idea of the altarpiece was a work to prove his abilities, is that the painting, with the St. Catherine of Alexandria, who was especially revered by the Dominicans, was painting with some connection to the Dominican church of S. Maria Novella and in particular to Rosso’s brother, Fra Costantino, who was a cleric there. The Servites also had a connection to the Dominicans, through St. Peter Martyr who helped in the founding of the order, and Rosso might also have thought of his painting as an altarpiece for the church of the Annunziata, where Rosso’s other brother, Fra’Filippo Maria, was a cleric. In this case the staff in the picture could have been St. Jacob’s in honor of Fra’ Jacopo, who again may have been of help here.

Remembering that the Angel Playing a Lute was once part of an altarpiece, what can be seen in its fragments gives evidence of a level of maturity, when Rosso was twenty or twenty-one, that is equal to, and possibly even greater than, Pontormo’s in 1514. Looking back, the Assumption of the Virgin of 1513–1514 seems a more novel and perhaps a more accomplished, if also a less passionate, work than Pontormo’s contemporary San Ruffillo Altarpiece (Fig.Pontormo, San Ruffillo).20 Rosso’s Angel approaches, in its small way, the degree of self-assurance of Pontormo’s Visitation, first paid for in December of 1514, which in certain respects is dependent on Rosso’s adjacent fresco. The difference in size of Rosso’s Angel and Pontormo’s Visitation makes, it is true, for a somewhat difficult comparison. Still, a detail of Pontormo’s fresco, such as the upper half of the woman carrying a bundle at the left, indicates in its drawing, foreshortening, modeling, and expression, approximately the same degree of ability that is presented by Rosso’s angel and his large lute. Among Rosso’s surviving works none presents the kind of accomplishment that is represented by the Visitation in Pontormo’s career. No work by Rosso up to this time reveals such a command of the most evolved artistic manner of Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo. Pontormo’s more focused education with Albertinelli and Andrea del Sarto gave to his art structural principles that, in spite of deviations, remained faithful to them: a plastic and spatial clarity used even in the expression of unusual states of being and feeling. Rosso’s art was not so singularly founded. His education seems to have been more fitful, resulting in artistic attitudes that, although at times novel, were also occasionally anachronistic and incoherent. It is as though he was distrustful of the sophistication of the most contemporary art, and, at the same time, impatient with the limitations imposed by its formality, even as he wished his art to be comparably grand. These conflicting views seem to have been responsible for some of the individuality of his art, including the significant differences between his little angel playing a standard size lute and Fra Bartolommeo’s single angel strumming a lute designed for his small size.

Between the likely date of the destroyed altarpiece from which the Angel Playing a Lute was cut and 26 February 1517, when Rosso matriculated in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali (DOC.2), no works by him are known, making it unclear just why his matriculation took place when it did. In June of 1515 Sarto was commissioned to replace Rosso’s Assumption in the atrium of the Annunziata, but this never happened. On 18 April 1517, the commotion over this fresco having settled down, the friars at the church, having now abandoned the decision to replace his Assumption, assigned Rosso another fresco in the atrium on the condition that he do better than before, but this painting was also never executed (see P.3). Nevertheless his status as a mature painter was confirmed by his matriculation suggesting divided opinion on his talent and achievement that was already indicated by the controversy among the clerics at the Annunziata.

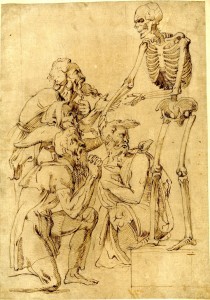

DISPUTATION OF THE ANGEL OF DEATH AND THE DEVIL

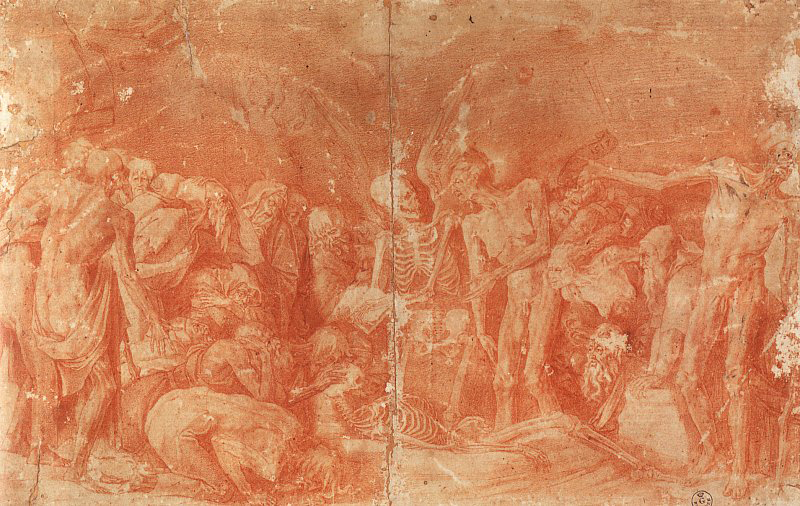

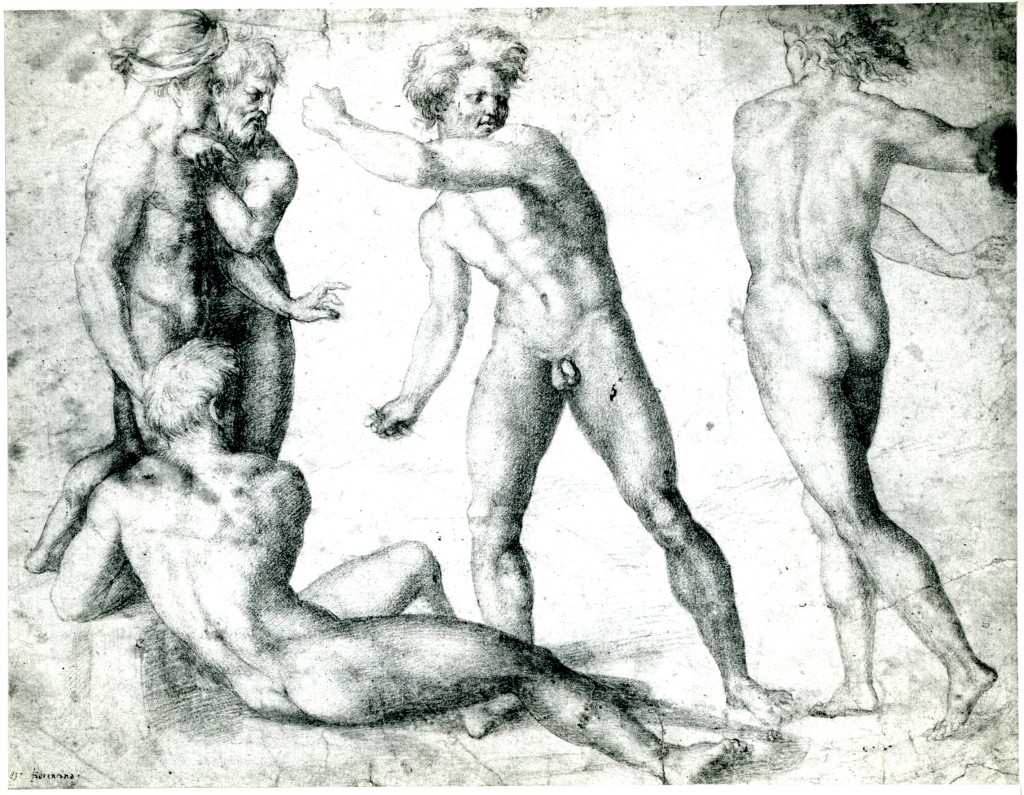

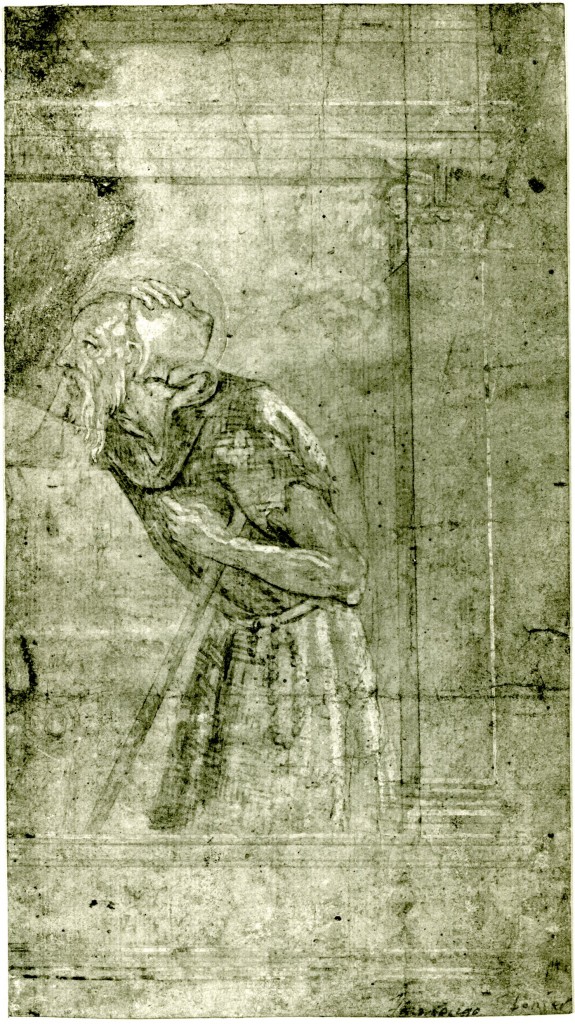

Probably later in 1517 he made the large red chalk Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil in the Uffizi (Fig.D.1a), as a disegno di stampa for Agostino Veneziano’s engraving dated the following year (Fig.E.109). In January of 1518 Rosso was commissioned to paint a large altarpiece for a chapel in Ognissanti, known as the S. Maria Nuova Altarpiece (Fig.P.5a) because of its subsequent ownership and now in the Uffizi, which was finished by the end of the year. From that year or early 1519 there also survives a Disputation Between Two Old Men, a drawing in the Uffizi (Fig.D.2). These three closely related works are significantly different from his earlier paintings and show new interests beginning in late 1514 or in 1515, suggesting contact with the work of Baccio Bandinelli.

Rosso probably knew Bandinelli well before this time. In his “Life” Vasari stated that Bandinelli, who was born just four months before Rosso,21 studied Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina, but in this context the biographer specifically mentioned, with a few other artists, “il Rosso ancor che giovane.”22 Rosso seems to have studied the cartoon around 1513 (L.3) and may have met Bandinelli then. However, Rosso could have met him earlier, through Rustici who seems to have frequented Sarto’s shop at the Sapienza at the time that Rosso was there around 1512. By early 1512 Bandinelli was assigned a fresco in the atrium of the Annunziata, the Marriage of the Virgin, it seems, and was fined in March of 1513 for not having done it.23 It was then assigned to Franciabigio who finished it by September of that year at the time that Rosso did his first work at the church. Just possibly Rosso may have known Bandinelli because of this Annunziata connection as well.

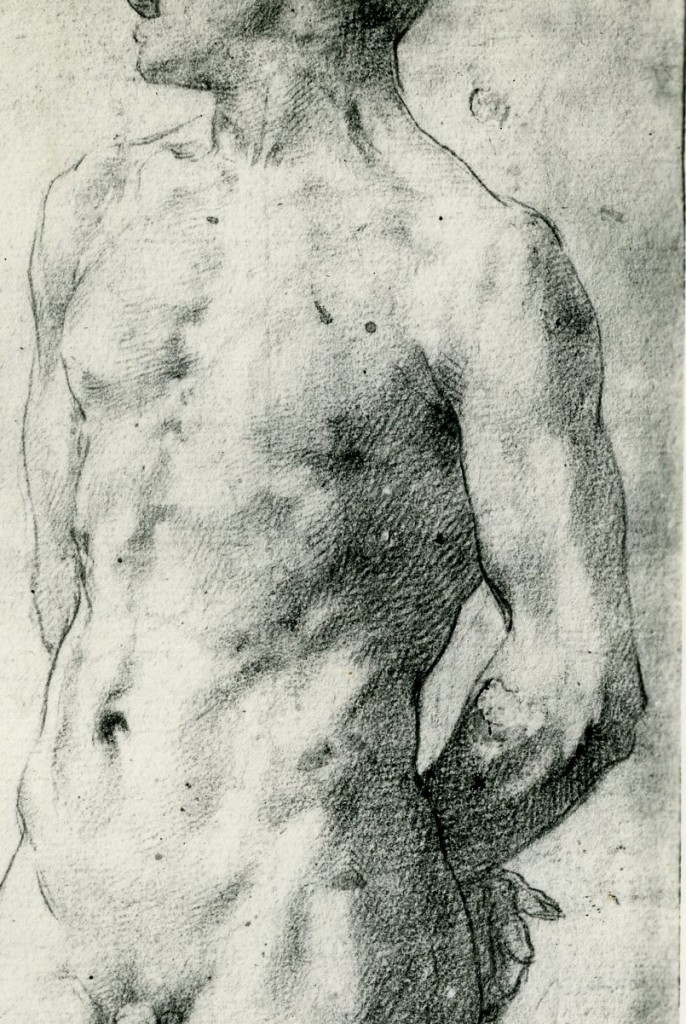

Bandinelli’s failure to fulfill the Annunziata commission was probably due to the fact (possibly only one of several, but certainly a very important one) that in 1512 he did not know how to execute a fresco. He also did not know how to paint in any other medium. In the “Life” of Andrea del Sarto, Vasari says that Baccio learned to paint in oil from Andrea and relates this story in a context that suggests the period between 1515 and 1517.24 This episode is connected with a portrait that Sarto painted of Baccio, a picture that has been identified with a painting in the Uffizi, or rather with the original from which it was copied, as is now thought. Sarto’s portrait has been dated around 1515 or 1516 on the basis of its style known from the Uffizi version and of the placement of the story concerning its execution in Vasari’s “Life” of Sarto.25 However, this account of the story is significantly different from the one that appears in Vasari’s “Life” of Bandinelli. Here Vasari says that Baccio’s attempt to learn how to paint by watching Andrea execute his portrait failed, but wishing still to learn “fu aiutato dal Rosso pittore, il quale più liberamente poi domandò di ciò ch’egli desiderava.”26 This story falls somewhat before the period around 1515 or 1516 in Bandinelli’s “Life” and it is possible that Andrea’s portrait of Baccio was executed somewhat earlier than has been proposed. In any case, by 1515 or 1516 Rosso seems to have been sufficiently friendly with Bandinelli for the latter to ask him for the instruction that he sought.

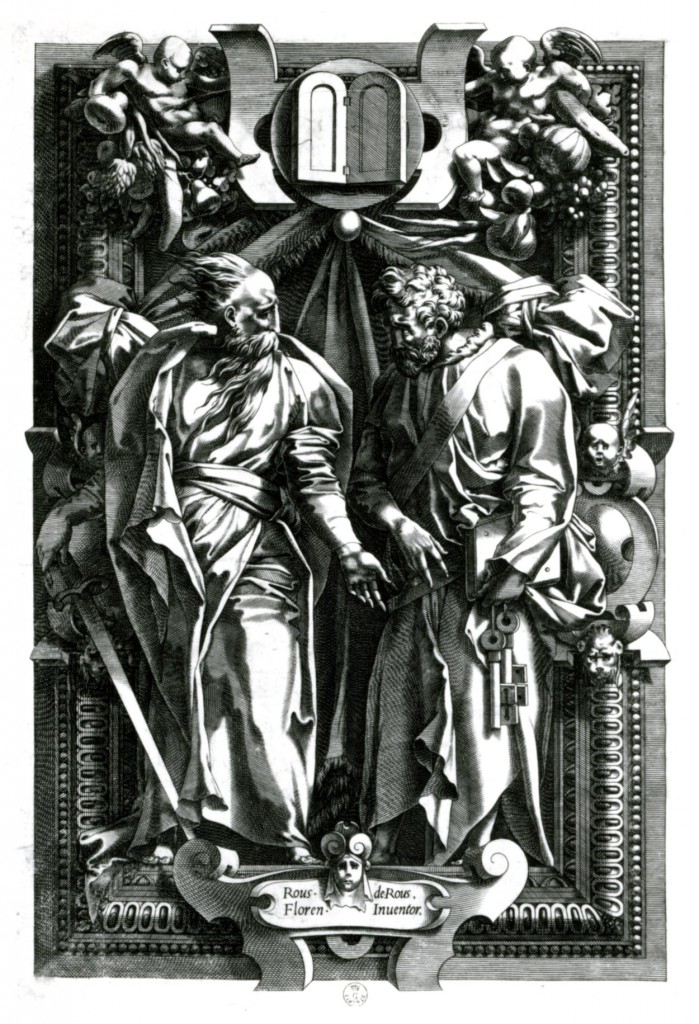

Although we know from Vasari that Baccio learned to paint from Rosso, what Rosso learned from Bandinelli, if anything, is not mentioned by the biographer. Hence a review of the education and early activity of the sculptor, as related by Vasari,27 may bear upon a possible relationship of his art and interests to Rosso’s in the period under consideration. At an early age Bandinelli began to learn to draw in his father’s shop and by copying the pictures in the churches in Florence. He also copied in wax some pieces of sculpture by Donatello and Verrocchio. Around 1503 or so he began to draw from life the nude workmen and the animals on the farm that his father had bought at Pizzidimonte, near Prato, where he also drew from the works of Fra Filippo in the cathedral. At some later moment he was put by his father into Rustici’s shop. There, late in 1507 or early in 1508, he met Leonardo28 who recommended to him the study of Donatello’s relief sculpture. Baccio also copied at this time an antique female head. As noted above, he then drew from Michelangelo’s cartoon at the same time as Rosso. From this account it can be recognized that before he entered Rustici’s shop, and still while there, Bandinelli’s attention was directed as much to the art of the preceeding century as to what was most modern in Florence in the first years of the sixteenth century. However, in 1508 or even earlier in this decade the new style need not, nor probably could not, have appeared to Baccio as quite so authoritative as just as few years later it would be to some. But even then Bandinelli looked back to the Quattrocento when, in 1515, he designed his St. Peter (Fig.RD.11) for the cathedral of Florence with Donatello’s St. Mark (Fig.Donatello, St. Mark) very much in mind.29 This look back to the Quattrocento could have attracted Rosso as sympathetic to an aspect of his own interests as seen in his Assumption of 1513–1514. (It should be remembered that about the same time that Rosso drew his Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil, Pontormo was giving his attention to the reliefs of Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise while executing four panels of the Story of Joseph for Pierfrancesco Borgherini, a project worked on by several other Florentine artists—Sarto, Granacci, and Bachiacca—but not Rosso.30)

By the time that Baccio asked Rosso to teach him how to paint, Bandinelli had, according to Vasari, “acquistato nome di grand disegnatore.”31 This and another detail of Vasari’s account of Bandinelli’s early career may have some bearing on an understanding of Rosso’s art in 1517 and 1518. Vasari says that the young Bandinelli “dettesi con grande e sollecito studio a vedere et a fare minutamente anatomie,” and goes on to tell us in the same paragraph that Baccio “messesi di poi a far di rilievo tutto tondo, di cera, una figura d’un braccio e mezzo, di S. Girolamo in penitenza, secchissimo; il quale mostrava in su l’ossa i muscoli astenuati, e gran parte de’ nervi, e la pelle grinza e secca….”32 This was in 1512, according to the biographer, when Baccio gave the relief to Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici upon the return of the Medici to Florence in the latter part of that year.

What role Bandinelli may have had in the shaping of Rosso’s interests as they appear in his Disputation of 1517 cannot be precisely documented. From what we know of Bandinelli’s own art up to that time it is difficult to see Rosso’s image as Bandinellian.33 However, until the end of the nineteenth century the drawing was attributed to Bandinelli, which seems to go back to Bartsch identifying him as the designer of Agostino Veneziano’s print made from it in 1518. But it is likely that in the 1560s Vasari already thought this. Twice in the Lives he mentions a print that is most likely the engraving of 1518 and assigns its composition to Baccio. This was, of course, fifty years after the drawing and print were made, over two decades after Rosso’s death, and a few years after Bandinelli’s long career had ended in 1560. From this perspective, having in mind drawings that Bandinelli had done since 1518, Agostino’s print may have looked as though it had been designed by Baccio.34 Such a mistake probably would not have occurred in 1518. It is possible that Vasari also thought the Disputation was designed by Bandinelli because it had been engraved by Agostino who had worked from several drawings by Bandinelli in the immediately preceding years.

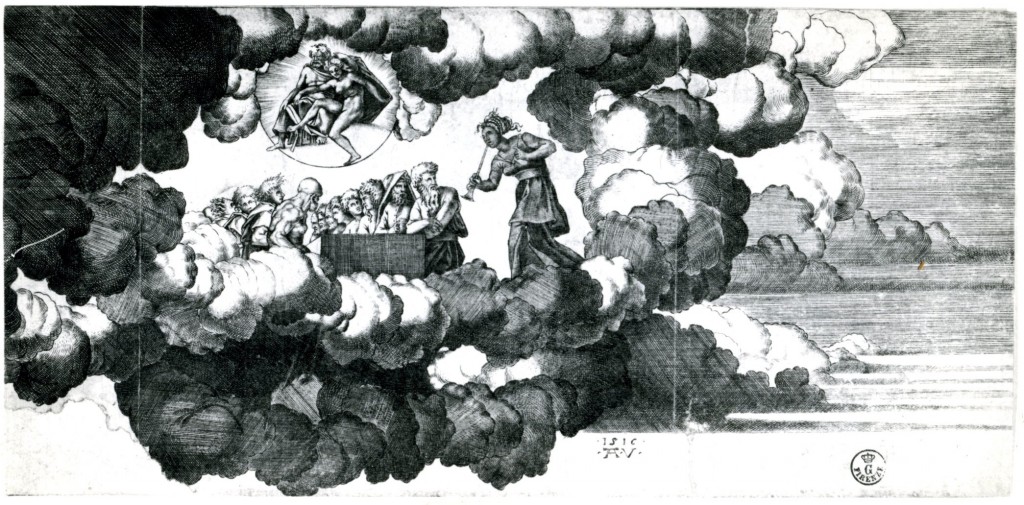

Nevertheless, a connection between Rosso and Bandinelli does seem to have existed which introduced Rosso to new artistic possibilities. These may have been stimulated not so much by the example of Bandinelli’s art as by certain interests that he had and brought to Rosso’s attention. One aspect of Rosso’s drawing does seem to be directly dependent upon Bandinelli’s art: the dense and dark manner of its draughtsmanship. While this is certainly related to the underworld depicted in Rosso’s drawing, the darkness of which is even deepened in Agostino’s engraving, there are a number of earlier drawings by Baccio of quite different subjects that are done in a very similar chiaroscural manner.35 There are also prints of 1515 and 1516 by Agostino Veneziano after drawings by Bandinelli, a Council of the Gods (Fig.Veneziano, Gods)36 and a Cleopatra (Fig.Veneziano, Cleopatra),37 that show the same kind of dark tonality. Given these resemblances and the connection with Agostino Veneziano, it is very likely that Rosso adopted this kind of draughtsmanship from Bandinelli. It was probably Baccio who introduced Rosso to the engraver.

In Bandinelli’s drawings this chiaroscural mode is clearly derived from Leonardo’s art, other aspects of which are also seen in some of Baccio’s works. One of his dark drawings, in pen and ink, is after Leonardo’s lost Angel Annunciate (Fig.Bandinelli, Angel),38 while other drawings in red chalk show heads with imitations of the Leonardo smile.39 A Leda composition of around 1516 also attempts a Leonardesque appearance.40 Remembering Bandinelli’s education in Rustici’s shop and his meeting with Leonardo in 1507 and 1508, sufficiently memorable to have been known to Vasari in the 1560s, the partial, but deeply considered, derivation of Rosso’s Disputation from Leonardo’s Adoration of the Magi (Fig.Leonardo, Magi), discussed below, very likely came about because of his momentary intimacy with Bandinelli. It is, however, possible that the earlier Portrait of a Young Woman as Mary Magdalen (Fig.P.1a) by Rosso may already show an interest in Leonardo’s art that goes beyond what could have been derived of its expression in Sarto’s work and which might stem from the interest in it shown by Bandinelli who by then had already studied Leonardo’s work.41 The regularizing of the composition of Leonardo’s Adoration seen in Rosso’s red chalk Disputation may reflect something of Bandinelli’s style as in his Announcement on Olympus engraved by Agostino Veneziano in 1516.

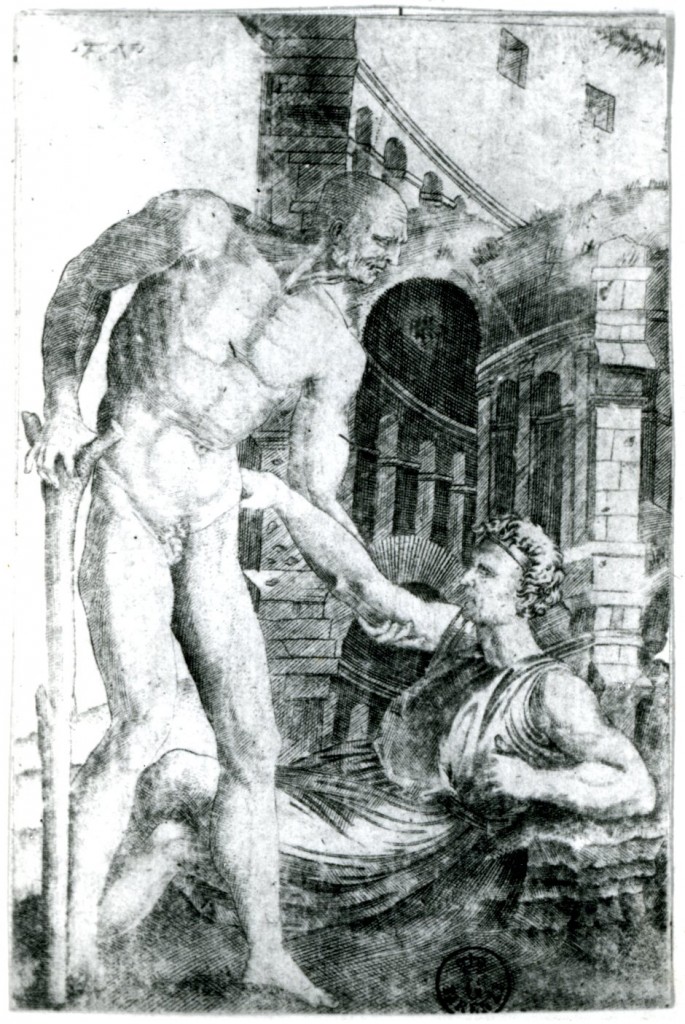

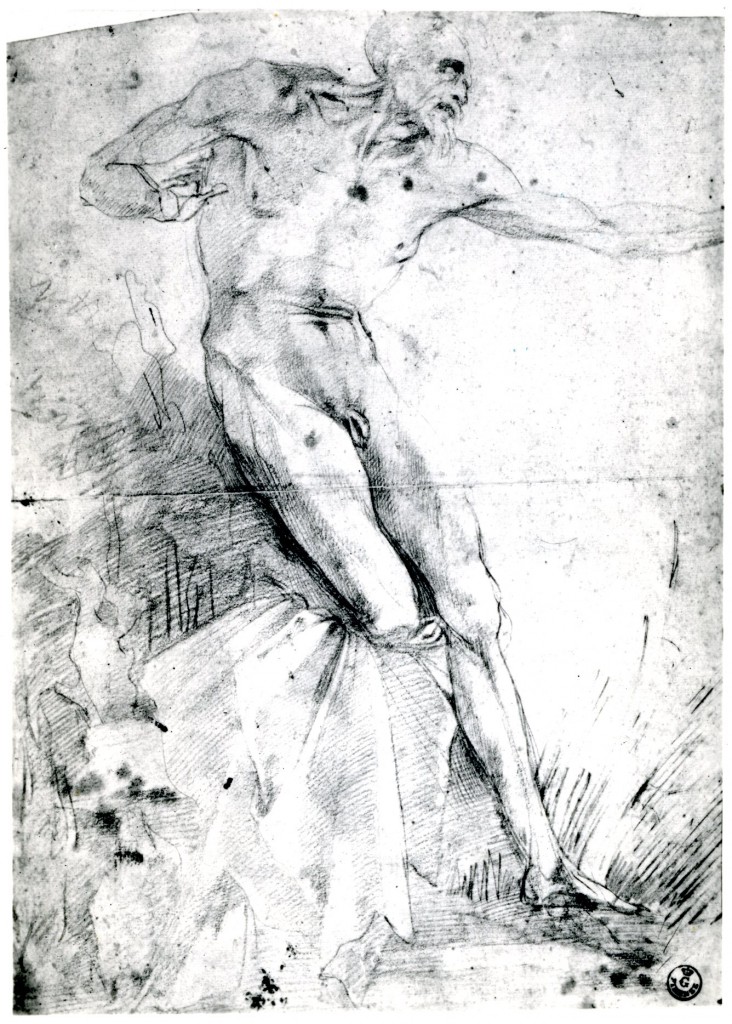

The emaciated and nude old figures in Rosso’s drawings could be related to Bandinelli’s interest in minutely described anatomy, as mentioned by Vasari, and which Baccio would have demonstrated in drawings and in his wax relief of St. Jerome in Penitence of 1512, which do not survive.42 However, there is a print by Agostino Veneziano of 1515 or 1516 after Bandinelli that shows an old naked man of the kind that Vasari, apparently, was describing (Fig.Veneziano, Old Man Helping Another).43 Another print of Two Disputing Philosophers (Fig.Bandinelli, Philosophers)44 also depicts thin old men, draped in this engraving, but here the dark tonality of the scene and its argumentative subject also bear a resemblance to Rosso’s much larger drawing. None of these images has the subtlety and complexity of Rosso’s drawing, and it would be hard to say that Rosso was imitating what Bandinelli had done. Nevertheless it is likely that what Rosso did came about because of his contact with Bandinelli.

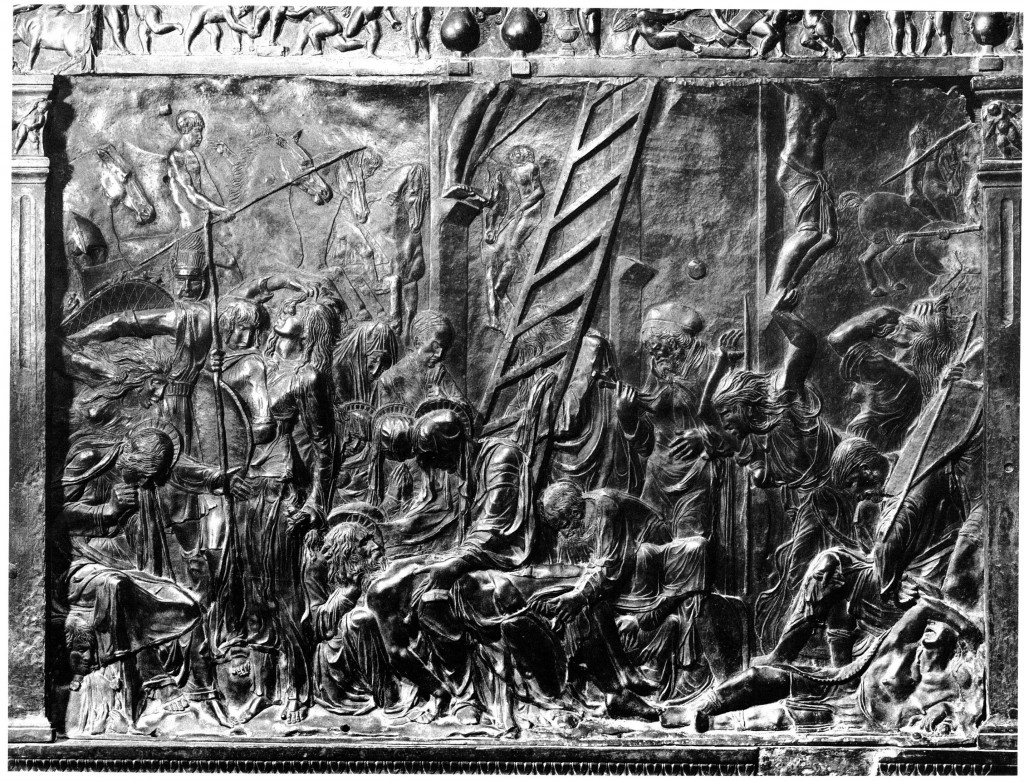

It may also have been through Bandinelli that Rosso became interested in the late works of Donatello. Vasari says that the very young Bandinelli copied works by Donatello in wax and that Leonardo advised him to study his reliefs. There are early drawings by Baccio that are derived from his pulpits in San Lorenzo,45 where they were set up in 1515 for Leo X’s visit in November of that year.46 A comparison of Rosso’s drawing with Donatello’s reliefs brings out no identical details.47 But Rosso’s emaciated figures do bring to mind the St. John the Baptist in the Christ in Limbo (Fig.Donatello, Limbo) of the North Pulpit, as well as his wood Magdalen in the Baptistery (Fig.Donatello, Magdalen) and the bronze St. John the Baptist in Siena (Fig.Donatello, Baptist). The composition of Rosso’s Disputation, rather shallow, crowded with figures in various postures around a reclining dead person—a skeleton in Rosso’s composition—and with a woman rushing in from the right, recalls Donatello’s Lamentation of the North Pulpit (Fig.Donatello, Lamentation), which thematically is also seriously related to Rosso’s drawing. The particularization of Rosso’s figures and a degree of their dramatic intensity, albeit more restrained, seem also to go back to Donatello. Thus while the Disputation is not so specifically like Donatello’s work as Bandinelli’s copies and derivations are, the emotional and thematic significance of the Disputation of 1517 appears deeply identifiable with Donatello’s reliefs. It may be Rosso’s friendship with Bandinelli that led the painter to look at Donatello’s work, but his response to it was very much his own.

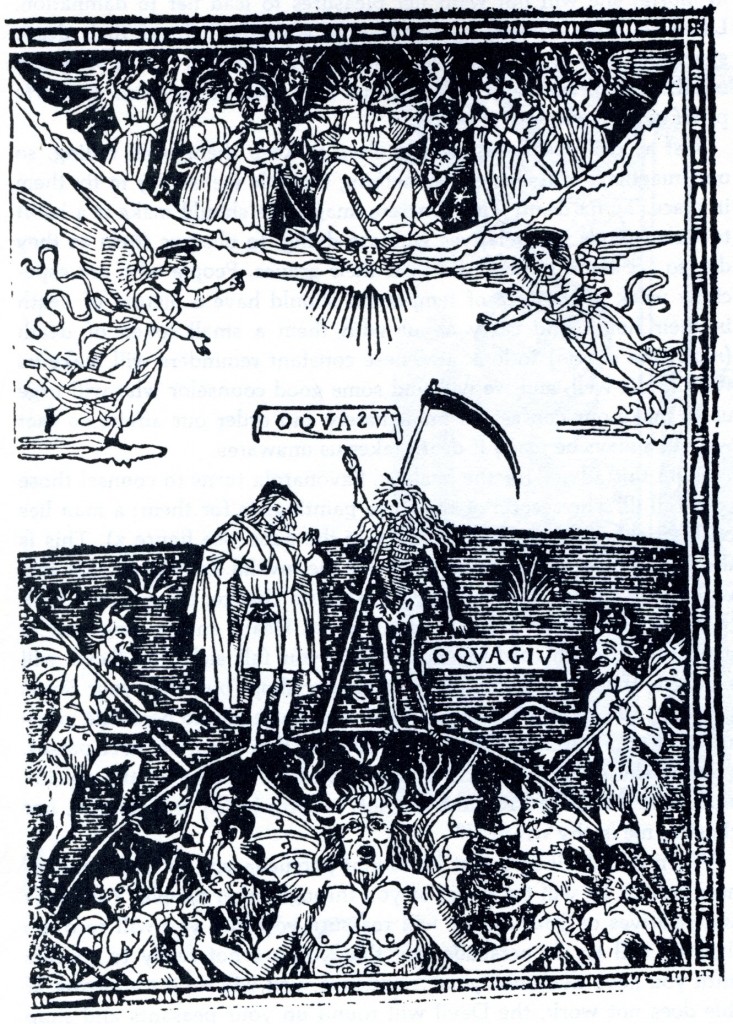

A few of Rosso’s figures and the hats with ear flaps and the hoods worn by some of them bring to mind details of Dürer’s prints, but such details are much more specifically quoted or closely followed by Sarto in his Preaching of St. John the Baptist of 1515 at the Scalzo (Fig.Sarto, Preaching), without, however, appearing especially Düreresque.48 The general darkness of Rosso’s scene, especially evident in some of Agostino’s prints, may also recall some of Dürer’s engravings, although earlier Florentine prints resembling nielli are similarly dark.49 Thus, while it is possible to associate Rosso’s drawing with the interest in Northern prints shown by several Florentine artists around this time, a direct comparison of these prints with Rosso’s Disputation presents no close similarities.50 There are greater affinities with aspects of Donatello’s bronze reliefs in San Lorenzo. Nevertheless, it is probable that in the Disputation Rosso was vying with something of the macabre in Northern engravings and woodcuts. But none of these Northern prints, fantastic as some may be in what they describe, nor any work of around this time by any artist in Rome or Florence, approaches Rosso’s image in the depth of meaning that can be associated with its particular bizarreness.

The possible sources of the style and of the character of Rosso’s drawing in the art of Donatello, Leonardo, Dûrer and other Northern printmakers, as well as Bandinelli, may at first seem unlikely in its multiplicity. When, however, Bandinelli was advised by Leonardo to study Donatello’s relief sculpture it would seem that he was recommending an art that he felt in some way was compatible with his own. In many respects of detail and of emotion and of dramatic intentions, Donatello’s Lamentation of the North Pulpit is similar to Leonardo’s chiaroscural Adoration of the Magi painted only fifteen years after Donatello died and possibly less than a decade after the pulpits were set up for the first time.51

It should be recalled that in the “Introduction” to the second part of the Lives Vasari stated his inclination to place Donatello in the Third Part of his book as he thought that the sculptor’s works were comparable to those of the ancients.52 Furthermore, in 1568 he ended his “Life” of Donatello with Vincenzo Borghini’s phrase: “Either the spirit of Donato worked in Buonarroti, or that of Buonarroti first worked in Donato.”53 To Vasari and Borghini and earlier to Leonardo, Bandinelli, and Rosso, Donatello’s art would seem to have been looked upon as modern, although it is possible that both groups of men were looking at different aspects of Donatello’s work. While Leonardo may have studied Donatello’s late reliefs, it is also probable that the San Donato Adoration of the Magi has also among its most serious precedents such a relief as Donatello’s considerably earlier Ascension of Christ in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Fig.Donatello, Ascension). Those aspects of Rosso’s drawing that are so different from what we think of as characteristics of the painting of Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo have a long history in Florentine art. For a while they were ignored, or surpassed, depending upon how the situation is viewed but only for a while if we recall that Piero di Cosimo’s latest and still very individual works were of very recent date. Within the context of this Florentine tradition the art of Dürer could be understood (as distinct from assimilated, which was Andrea’s manner of dealing with this interest). For it needs to be remembered that part of the origins of Dürer’s own art goes back, via Mantegna and Bellini, to Donatello. In studying Dürer’s prints Rosso and Bandinelli would not have been looking at an art wholly divorced from that of the quattrocento Florentine sculptor. In its seriousness and brilliance of invention Dürer’s art could hold its own alongside Leonardo’s Adoration. Read in one way the history of Florentine painting culminates, through Leonardo, in the works of Sarto and the Frate. But looked at somewhat otherwise and more as Rosso seems to have looked at it, the history of Florentine art led, also through Leonardo, to possibilities of quite different modes of expression. These may consciously have contradicted the modes of Sarto and Fra Bartolommeo, but it may not have been Rosso’s primary intention to do quite this. Other feelings, intuitions, experiences, and issues continued to exist that could and eventually did demand kinds of art not like Sarto’s and Fra Bartolommeo’s, or Michelangelo’s and Raphael’s.

Done probably after he matriculated into the Guild of Physicians and Apothecaries on 26 February 1517, and possibly after the abortive commission of another fresco at SS. Annunziata on 18 April of that year, the Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil is Rosso’s most significant achievement since the Assumption of the Virgin of 1513–1514, although a destroyed altarpiece of late 1514 or 1515 would have intervened. In spite of its small size compared to his earlier fresco, the complexity of the conception and the fineness of the execution of the Disputation make this drawing his most remarkable work to date. But it is not a small drawing and the same size as the large print that was made from it. Its large size as an engraving would seem to indicate the recognition that there was an audience for Rosso’s special talents and for this very unusual image, invented to be engraved by Agostino Veneziano and issued in numerous impressions. Agostino could have engraved the disegno di stampa in Florence on an otherwise unrecorded trip there—his only print dated 1518—indicating that the print could have been done in close collaboration with Rosso,54 as in the case of the many prints later made by Caraglio in Rome from Rosso’s drawings. Thus it is the print, in the opposite direction of the drawing and with slight changes, that would have been envisioned as the finished work of art, as would have been the situation with the prints made in Rome.

The Disputation of the Angel of Death and the Devil marks the beginning of a new level of sophistication in Rosso’s art, but one which, for all its novelty, is still bound to the past. In this case the past is represented by Leonardo’s Adoration of the Magi of 1481. What is at first evident is the similarity of types of old figures and their various postures, gestures, and expressions of adoration and attention directed toward a central event. Rosso also found in Leonardo’s work the means of massing his figures and differentiating them to give compositional coherence and the sense of a continually unfolding drama. Rosso, however, limited Leonardo’s space and created instead a more relief-like composition, recalling, it would seem, Donatello’s reliefs. Possibly following Bandinelli’s art, he reduced the range of human types and fixed them into poses that are stiff and angular, and hence without Leonardo’s grace of body and mind. While the darkness of Leonardo’s picture is a penumbra from which the forms of the figures within it arise and are made visible to us in the light, in Rosso’s drawing the darkness seems a condition of the underworld event that he represents. Where all of the diversity in Leonardo’s painting enriches and brings its meaning to bear upon a central image of benevolence, Rosso’s figures fanatically fix their attention upon a macabre argument concerned with the terms of Death. By what seems a comparably macabre sleight-of-hand the terms of Leonardo’s art have been warped and caused to shrink but without losing entirely their original identity. An intensity similar to Leonardo’s remains, as well as a similar detachment from ordinary experience. But whereas Leonardo appeared concerned with the expression of the rising consciousness of the most profound sense of joy and love, Rosso was concerned with the evocation of death and of a wasted and desolate humanity, attended by a dispute between a smiling Angel of Death and an arguing naked Devil over the dead man’s survival based on the evidence recorded in the huge book the Angel holds.

The drawing has the aspect of both an Adoration and a Pietà, bringing together, as it were, elements of both Leonardo’s large painting and Donatello’s Lamentation in San Lorenzo. Reclining motionless on a ledge of rock in the foreground is a skeleton occupying the position generally held by the dead Christ in a Pietà. This skeleton seems to represent a person who has been long dead. He is missing his lower jaw. Above him is another skeleton, a live one with wings, who, given the position of his knees, would seem to be standing in a pit or a grave behind the ledge of rock. Holding a book, this upright skeleton appears to be the image of Death; but with his large bird’s wings he is not, in 1517, the usual Italian representation of him.55 Furthermore, he does not have a scythe. He is about to turn some pages in the book he holds to the left, but his head is turned to the right, and with a broad smile on his face he talks to an emaciated figure with sagging breasts and male genitals. (These directions are reversed in the engraving, and seem there to be as intended because the major gestures appear more appropriately right-handed). Panofsky identified this figure as the Devil, correctly, it would seem, because of its sexual ambivalence.56 In this respect he is different from the comparably thin and nude old man at the far right who does not have a woman’s breasts. The Devil seems, as he gestures, to be presenting a serious argument to Death. Next to him rushes forward a nude old woman with pendulous breasts probably representing Envy (or Hatred), as Panofsky pointed out. The other figures in the composition are not so precisely defined. The figures at the left appear in simple clothing, some ragged, a few adoring and worshiping the reclining skeleton, others giving their utmost attention to the argument taking place between Death and the Devil. At the right and mostly behind Death and the Devil the figures are, insofar as one can see their clothing, better dressed; even the nude old man wears a fine hat, more fully visible in Agostino Veneziano’s print. On either side and in profile is a bearded man wearing a cap with ear flaps; the one at the left, shabbily dressed, pulls his hat back off his head and puts his right hand on his breast, the other man bends forward and supports himself firmly on his arms and hands that press down on a large rock. One man bent over at the left wears a cloak and hood. Most of the figures are old, some very old, though a few youthful heads can be seen. Whatever is taking place here is unrelentingly serious.

Panofsky, reading back from Bernini’s imagery of the seventeenth century and then relating this imagery to documents contemporary with Rosso’s drawing, interpreted Rosso’s Disputation as a vindication of the character of Savonarola who had been falsely accused, condemned, and executed in Florence just twenty years before the publication of Agostino Veneziano’s print. But the evidence Panofsky called forth is not conclusive and the drawing itself contains no explicit reference to Savonarola, or, for that matter, to Christianity.57 Nevertheless, it is very possible that the scene is about the vindication of a reputation, although not necessarily a particular one. Rosso’s configuration of Death as a skeleton with bird’s wings is not unique, but it is sufficiently rare to make one wonder about its origins and precise meaning. The wings make him appear more as a benevolent Angel of Death than as a demon, as Panofsky pointed out. His expression does too, difficult as it would be for a skull to smile. Having no scythe, he has come not to destroy but to grant an everlasting existence on the basis of the record of the deceased kept in his book. The wings, therefore, are probably a reference to Time. Why the deceased is represented as a skeleton rather than a cadaver is puzzling, but it is possible that it is to signify the eternal death of the body. Triumphant over this death is Death-Time who, by having recorded the accomplishments of the deceased in his book, grants him immortality through Fame. Death-Time’s argument is made for the deceased who cannot make one any longer for himself, and hence his depiction without a jawbone. On the other side of the argument is the Devil, whose victory would signify eternal oblivion. In this case he is not the Christian Satan but a secular equivalent whose unsuccessful dispute with the Angel of Death results in another kind of eternal life. Similarly, Rosso has borrowed from the Christian scenes of the Adoration and Lamentation to give comparable significance to other aspects of this secular subject.58